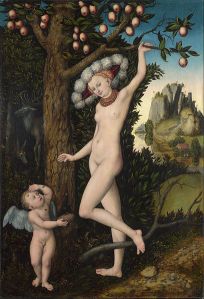

The image above – Cranach’s ‘Venus,’ painted in 1532 – might be familiar to you from exhibition posters of a few years back. In 2008, the Royal Academy put on a show dedicated to Cranach, and this tiny painting, blown up to poster size, was briefly pasted all over the London Underground as an advert … until somebody complained. I remember the debates this story sparked, with some arguing that the painting sexualises a pubescent female body, others claiming that any female nude is unacceptably objectifying, and others again insisting that we cannot judge Renaissance art on the same scale as we judge other images. One thing was clear: people reacted far more strongly to this image – whose context is the German Renaissance – than they might have to the more familiar image of Venus by Botticelli or Raphael. Because this image was more unfamiliar, its details seemed more stark and more shocking.

Some of the same debates were in my mind this weekend, when I went to the National Gallery to see their current exhibition – ‘Strange Beauty: The Masters of the German Renaissance‘. Like the earlier exhibition, it’s fronted by a Cranach nude, in this case ‘Cupid Complaining to Venus’.

I’ve seen no evidence that the use of this painting to advertise the exhibition raised any complaint at all, so it’s my sad duty to break it to you that there really isn’t an international feminist conspiracy to censor all art everywhere. Yes, I know. And Santa isn’t real. But what I didn’t know before I went to this exhibition was that there’s a long history of objections to Cranach’s work, rooted in a rather different set of prejudices and concerns.

In the nineteenth century, when the National Gallery opened, there was a sense that German Renaissance art was ugly and inferior to the work of Italian artists. Would-be donors, including Prince Albert, tried quite hard to foist some of their collections on the gallery, who responded that they Knew Their Stuff and didn’t want any of this Cranach shite when they could be buying Botticelli.

The first couple of rooms in the exhibition were set up to demonstrate the limitations of this attitude, and they were fun. Panels of an altarpiece were set out so that you could walk around them, seeing the inside and outside. Another altarpiece showed Joseph grumpily rummaging in his purse for coins to pay the priest at the temple for the infant Jesus’s presentation. The real-life context of these paintings was obvious: you couldn’t help seeing their function as objects in front of which people would have knelt and prayed. This impression was deepened by the painstaking realism of small details: you could read the pages of the books of music and arithmetic in Holbein’s ‘The Ambassadors,’ and pick out the neat secretary script on a roll of paper clutched by a town clerk in his portrait. The attention to detail carried through to intricate prints and tiny, beautiful pearwood game-pieces, which featured portraits of their owners. The famous picture of Anne of Cleves is one of these, and it’s about two inches across.

All of this realism, though, contrasted sharply with what nineteenth-century curators of the Gallery had seen as the ‘ugliness’ of German Renaissance art: its asymmetry, its distortions and stiff postures. This was exemplified by the depiction of the Virgin. Where Italian madonnas are often young and beautiful, here there were pictures of Mary represented as an older woman with her face distorted from weeping, with her body twisted in sorrow, displaying heightened, almost grotesque emotion.

What was fascinating about seeing all of these paintings together was that you could trace the influences both of the realism and detail, and of the asymmetry, in the portraits of real people that hung alongside the religious art. The portraits by Holbein (but also by other German masters, some of them anonymous) showed tilted half-profiles with quirked lips or slightly raised eyebrows, with meticulously realized details. They seemed real, alive, arresting.

In this context, the Cranach Venus looked, to me, oddly insubstantial, and her symmetrical face and graceful pose seemed bland or oblivious rather than suggestive. The painting was unsettling in a way it might not have been if I had seen it surrounded by similarly beautiful and calm Italian Renaissance women. I’d expected to find this painting easier to respond to when surrounded by contemporary work by other German artists, but instead I found it more enigmatic.

The contrast between Cranach’s idealised Venus and the portaits of other women around the room was striking. I concentrated on this of princess Christina of Denmark, painted by Holbein in 1538 for the newly widowed Henry VIII. At this point Henry was 47, and on the lookout for wife number four. Christina was sixteen, and already a widow.

Dressed in sumptuous billows of dark fabric, fur edging and a demure widow’s cap, Christina gives the impression both of physical stature, and status in the world. It is a complete contrast to Cranach’s slim, child-like, naked Venus. In fact, these clothes look most similar to those of the richly dressed men whose portaits hang around the room. Near to Christina stand ‘The Ambassadors,’ painted by Holbein just a few years before and immortalizing two French diplomats in England.

The two men look, like Christina, older than their years: Georges de Selve, on the right, was just twenty-five when this picture was painted, less than a decade older than the sixteen-year-old princess. His dark, rich, fur-trimmed clerical robes echo Christina’s mourning dress, and it’s hard not to read both her clothing and her direct gaze as another kind of diplomatic statement, aligning her with these negotiators rather more than with the Venuses and saints who surround her.

This interpretation is one you can feed back into Christina’s history, too. As a teenager, after her first marriage ended, she lived in the court of her aunt, Mary of Hungary, who was governor of the Low Countries and a powerful woman in her own right. In 1541 she married the duke of Lorraine, and after his early death she acted as regent for their son Charles. She spent most of her life engaged in the same sorts of struggles for power that her male counterparts were busy with, and by the time she died, aged 69, her legacy was secure. She had fourteen surviving grandchildren, and the royal families of three (plus?) countries are descended from her, and her oldest son was married to Catherine de Medici’s daughter. Wiki has a really snide article on her, which alternates between representing her as an unsuccessful schemer and a Machiavel, and raises my cynical feminist antennae. If we compare her to Henry VIII and his children, who ruled England during her lifetime, she comes out pretty well.

It might surprise you to find that there’s a really creepy description of this painting in the Telegraph‘s review of this exhibition, which describes it as “an icon of quiet but intense eroticism” and suggests that “somehow, we are tempted into imagining her body underneath”.

Ahem. We?

I found this – and especially that tone of complicity – really grating, much more so than any comments on the Cranach nudes could have been. It seems to circumscribe Holbein’s painting, reducing the subject to a position of minimal agency, defined by her fleeting connection to an English king. For the negotiations that this picture reflect were soon ended: Christina rejected Henry’s offer, and throughout her life she spent far more time as regent than she spent as anyone’s wife. I know there are lots of paintings of medieval and Renaissance women that don’t come with so much historical backstory. Sometimes – as with Cranach’s Venus – we know nothing at all about the woman who posed for her painting. But this exhibition made me wonder how much we really know about what medieval and Renaissance viewers judged to be erotic or beautiful, ugly or grotesque, and how much we distort their work in our mind’s eyes to make it fit our expectations.

Note

I’ve limited the number of images in this post, partly because not all of them are on wiki commons and partly because you ought to go find them – if not at this exhibition, on the National Gallery website. However, I really wanted to know what the grid of numbers in the background of this etching of Melancholia was meant for, and if you might know, please have a look and tell me!

The grid of numbers behind Melancholia is a magic square.

See http://mathworld.wolfram.com/DuerersMagicSquare.html

Ahhh … I thought you might well know! A man looking at it with me commented ‘I didn’t think they had sudoku back then!’ but we decided that it probably wasn’t that …

There are also various things that appear to be out of kilter, and possibly a source of melancholy: an abandoned carpentry projict, a starving greyhound(?), a lovely irregular octahedron and I think an hourglass with time running out. Melancholia is attempting to use a pair of dividers on her lap, which sounds like another recipe for trouble.

Yes, I’d love to see that exhibition!

Oh, you should go – I thought it was really good. There is a portrait of a woman from the Hofer family (that’s all the inscription tells us about who she is), which is really clever. And lots of other good things, but that stood out and virtually every review I’ve read has reproduced it – which is why I haven’t here!

I’d not noticed the octahedron …

Basically, it really is pretty much like Soduku. All the squares have to add up to the same total, in this case 34.

I shall stop filling up your blog forthwith.

No, you’re welcome to continue! At some point, I would love to post a little bit about the history of maths.

And I would love to read that! As soon as I saw the square I assumed it was magic-related (I’ve taught an ancient magic course for the last few semesters) – math and magic were so closely linked early on (e.g. Pythagoras, the great mystic), and ancient Greek, like Hebrew, used letters for numbers, so the numerology is pretty well built in (mostly it was all about allegorical interpretation of texts, but also some divination and such). I know that’s all a bit far afield, but I tend to do that, sorry…

Oh, that course sounds so much fun! You very likely know much more about it than me. I was planning to lean on my brother (who teaches a history of maths course) for a guest post, but it might be some time. I always think it is interesting how much practical maths some people must have had, maybe even without knowing how to write it down.