In my previous post, I got halfway through the Roman de Silence, the story of the woman Silentius who was brought up as a man by her parents. Silentius is so successful as a man that hordes of women end up swooning over her, and Nature finally gets so furious about this that she descends on Silentius and insists she should act more like a woman instead of tempting women into same-sex attraction. This form of ‘correction’ is pretty familiar to us in the modern world, and it’s not just aimed at cross-dressing women. Like Silentius, we might think what we’re doing has nothing to do with sexuality – after all, in the romance, all she’s doing is training to be a knight – but, to the patriarchy, that’s a problem in itself: women must be reminded that everything they do is to do with sexuality. And if it’s not overt heterosexuality, it needs to be set straight. And this is what Nature tries to do with Silentius. Unfortunately for Nature – and I’m honestly not making this up though it sounds like something written in 1972 – Nurture then turns up and shouts Nature down. Silentius goes off to the court, where King Evan (yes, really. I picture him in a nice turtleneck) is holding a tournament.

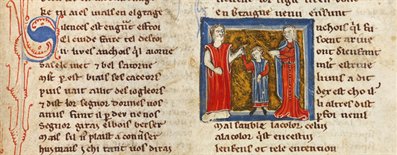

As you can see from this image, tournaments weren’t just about men fighting, they were also about women watching. Some scholars reckon that, just as a few women (not me, of course!) watch Game of Thrones not purely for the intellectual pleasures of George R. R. Martin’s plot devices, so too some women might have read about tournaments not just because they wanted to be sure men were being properly trained for war. The positions of these women’s hands certainly seem to suggest they were comparing notes on a very important six inches. Anyway, in the Roman de Silence, one of the women watching is King Evan’s wife, Queen Euphemia. Being unwomanly and lustful and all sorts of other inappropriate things, Euphemia toddles off to proposition Silentius and is shot down by our heroine. In revenge, the queen tells her husband she’s been raped and that Silentius must be punished. This delightful ‘bad woman cries rape’ plotline isn’t unprecedented in medieval romance – Guinevere does it too – and it allows the narrator to turn Silentius’s cross-dressing into a positive moral force. Inevitably, in the process of proving that women cry rape to the satisfaction of the court, Silentius is outed as a woman. Barely has she whipped off her false ‘tache before King Evan sweeps her off her re-feminized feet and marries her. It’s a speedy turn of events that leaves us with the strong suspicion it wasn’t only the queen who went to the tournament to eye up cute young things with muscly thighs.

Matthew Paris, Historia Anglorum, England (St Albans), 1235-1259, Royal 14 C. vii, f. 124v. Henry III marrying a glum-looking Eleanor of Provence

The story of Silentius isn’t unusual in the way it represents women cross-dressing. In King Arthur’s court, a woman knight called Grisandole gets on nicely with her career until Merlin decides to ‘out’ her. Blanchardine, a woman who converts from Islam to Christianity, dresses as a man to protect herself. She marries a woman and is ‘rewarded’ for her piety by being magically transformed into a man. The best of all is the Princess Yde, who isn’t just turned into a man when she marries a woman – she also impregnates her wife and becomes patriarch of a dynasty of Emperors of Rome. The common theme in all of these stories is that the women are successful cross-dressers; they’re convincing men. To put it another way, the speak the language of their oppressors. They understand how to ‘man up’. That’s what makes these women dangerous to a misogynistic culture. Inevitably, the narratives end by showing us heterosexuality restored once more – ideally, fertile heterosexuality. To us as modern readers, it could be disturbing to see this presented as a ‘happy ending’. But it’s not a story about masculinity triumphant and heterosexuality the undisputed winner. The king who insists only boys should be able to inherit is aggressively pro-male, but his politics seem to be more than a little bit personal. At best, he’s a cuckold; at worst, he’s been eyeing up the young men while his wife looks for sex elsewhere. And I think it’s this sexist stereotype that the romance is really bothered about. Just to end, I wanted to think about why medieval stories are (almost?) always about women dressing up as men. And there’s an image, and an anecdote, that shows us why:  I found this picture of St Jerome cross-dressing on an amazing tumblr account. As the story behind the picture goes, the eminent saint and star misogynist of previous posts was considered a bit of a stick-in-the-mud by his fellow clerics. While he slept, they dressed him up in women’s clothing. When he woke up, he made his way to church as normal only to discover belatedly that he was, in fact, got up like the Virgin Mary only hairier. Apparently, the dire shame accounts for his bitter demenour. Jerome is, needless to say, not a successful cross-dresser, any more than King Evan is allowed to toy with the idea of a little homosexual fling with his knights. Medieval romances, like modern tabloids, enjoy playing with the idea of a little temporary lesbianism or a touch of sexy cross-dressing from the women in the narrative. It’s tempting, as an academic, to read these romances as safe spaces for women to explore sexuality, or places where gender can be ‘performed’ in different and exciting ways. But it’s also to ignore a more serious issue. In our cultural narratives (now as in medieval England), there is space for women to play at being a little bit masculine, a little bit lesbian, so long as that play is ultimately resolved. This doesn’t give women greater freedom. It erodes the idea of female identity and sexuality as equal to and as important as male identity and sexuality.

I found this picture of St Jerome cross-dressing on an amazing tumblr account. As the story behind the picture goes, the eminent saint and star misogynist of previous posts was considered a bit of a stick-in-the-mud by his fellow clerics. While he slept, they dressed him up in women’s clothing. When he woke up, he made his way to church as normal only to discover belatedly that he was, in fact, got up like the Virgin Mary only hairier. Apparently, the dire shame accounts for his bitter demenour. Jerome is, needless to say, not a successful cross-dresser, any more than King Evan is allowed to toy with the idea of a little homosexual fling with his knights. Medieval romances, like modern tabloids, enjoy playing with the idea of a little temporary lesbianism or a touch of sexy cross-dressing from the women in the narrative. It’s tempting, as an academic, to read these romances as safe spaces for women to explore sexuality, or places where gender can be ‘performed’ in different and exciting ways. But it’s also to ignore a more serious issue. In our cultural narratives (now as in medieval England), there is space for women to play at being a little bit masculine, a little bit lesbian, so long as that play is ultimately resolved. This doesn’t give women greater freedom. It erodes the idea of female identity and sexuality as equal to and as important as male identity and sexuality.