Medieval children: they were almost all boys, you know. Pleasantly, the image illustrates text from the massacre of the innocents.

French breviary, c. 1320–25. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 2, fol. 142.

Despite the title, and doubtless to the relief of my mate’s brilliant daughter who gently suggested it might be time to knock the penis posts on the head for a bit, you will be pleased to know this isn’t another post about medieval genitalia. The quotation is from the famous scene from Blackadder II, which was running through my head as I watched a documentary about medieval childhood yesterday.

Nursie: Out you popped and everyone’s shouting: “It’s a boy, it’s a boy!” And somebody said: “But it hasn’t got a winkle!” And I said: “God be praised, it’s a miracle. A boy without a winkle!” And then Sir Thomas More pointed out that a boy without a winkle is a girl. Everyone was really disappointed.

Melchett: Yes, he was a very perceptive man, Sir Thomas More.

Sir Thomas More, by Hans Holbein the Younger. Engaging in reductive biological essentialism since 1478.

I’ve got to admit, it’s not the first time I’ve felt as if noticing the existence of girls as well as boys is an act of quite exceptional perceptiveness. At a seminar last week run by the brilliant Rachel Moss, we discussed how often anonymous medieval poems are attributed to men rather than women; how often the masculine experience is imagined to be the default. This is especially the case when the experience in question is something we value as a society: fighting wars, writing books, earning money. By simple omission, we fail to attribute to women the historical identities that male figures are given, as active participants in their society. And as I watched this documentary, I felt the same.

It was a pity, because it was absolutely fascinating in many ways, and I would recommend it. But I did have one quibble, as you might have guessed. It was (almost) all about boys.

To be fair, a couple of girls did show up briefly, notably Margaret Beaufort, whose function in this documentary was to imply that, if you were not of the be-penised tribe, your fate was a traumatic pregnancy aged 12 and, whoopie-do, the conception of The Tudor Heir. The precise phrasing was, in fact, ‘Margaret was just one of millions of medieval children who made a vital contribution to England’s transformation’. This documentary implied (and I’m sure it wasn’t deliberate) that the only experiences girls participated in were playing, dying, and being married off at a young age. I can’t help noticing those are all economically passive activities.

I found this very uncomfortable viewing, a jarring note in what could have been a brilliant exploration of medieval boyhood. I couldn’t really understand why some of these childhood experiences were being discussed purely in terms of boys. Most of the childhood experiences described – going to a monastery to be trained up for the religious life, going to the manor to learn to be a servant, working as an apprentice or helping out on your parents’ farm – were common to boys and girls.

Yes, you can feed the chickens with a distaff tucked under your arm, but you do risk creating monster giant sparrow-style mother hens.

Detail of f. 166v in London, BL MS Add. 42130, f. 166v. c. 1320-40.

So, to counter some of the assumptions we’re often led to make about medieval girlhood, I wanted to look at one specific situation: that of growing up as a female apprentice learning a trade.

In London as in other big cities in the fifteenth century, girls aged 14 or even younger could seek apprenticeships – some acting apparently on their own behalf, others aided by parents or relatives. These girls were often placed with families whom they’d known from early childhood, and apprenticeship could last as much as seven, or even ten years. Effectively, then, apprenticeships bridged the gap between childhood and full maturity in the same way adolescence does now, though some girls evidently left to get married midway through.

Women spinning and weaving together in Boccaccio, Le Livre des cléres et nobles femmes. From Paris, Bibliotèque Nationale de France, MS Fr. 12420, fol. 71. c. 1403.

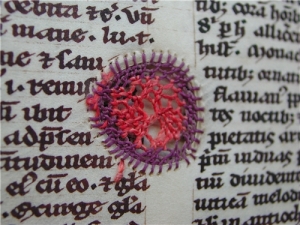

Many of the trades in which girls were apprenticed had to do with what we would still imagine as ‘traditionally feminine’ crafts: silkwork or embroidery, clothmaking or spinning. Perhaps more unexpectedly, though, some girls were obviously competent enough at reading and writing to go into literate trades, like the orphaned daughters of John Shaw, Alice and Matilda, who were apprenticed to one Peter Churche, a notary public. Indeed, it’s possible traditionally ‘feminine’ sewing and traditionally ‘masculine’ writing weren’t such different spheres of activity after all:

Medieval manuscript mended with embroidery. See http://www.ub.uu.se/en/Just-now/Projects/Completed-projects/A-medieval-book-mended-with-silk-thread/

This evidence of professional literacy amongst female apprentices made me think back to that anonymous poem I’d been reading in the seminar. The poem is called The Assembly of Ladies, and what’s interesting about it is that it may not be a story about adults, but about adolescents. Rachel Moss explains that the poem’s opening description of women finding their way through the garden maze evokes the highly conventional masculine ‘coming of age’ scene of a young boy finding his way through the winding paths of a forest, which was well known in medieval romance. In addition to this, the women of the poem are dressed all in blue – the colour of faithful love, but also of virginity, perhaps symbolising their youthful state. The central part of the poem is taken up with a description of the mysterious court of ‘Lady Loyalty,’ who listens to each woman’s views on love (an appropriate topic if we believe marriage to be a crucial rite of passage through which medieval girls founded their identities as adult women).

Virgo dressed in blue. From the Belles Heures of the Duc du Berry. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954, 54.1.1).

I was struck by the fact that, in the introduction to this poem, the editor Derek Pearsall comments that the many descriptions of clothing might be supposed, stereotypically, to appeal to women. I read this initially as a comment on women as consumers, women as wearers of clothes. But when I thought about young women apprentices, perhaps sitting listening to this poem read aloud in a house is medieval London, I could imagine them listening with a professional ear, imagining the making of such clothes. You see, in the poem, each woman literally wears her ‘heart on her sleeve’: each has an embroidered motto on the sleeve of her gown.

Such devices existed in real life, and it’s quite possible that female apprentices learning embroidery would have made such embroidered sleeves themselves. I couldn’t find an example contemporary with the poem, but this tapestry made a few decades earlier includes a motto, made up of rather stylised letters scattered over the hanging blue sleeve of the middle lady, which read ‘monte le desire’ (‘desire grows’).

‘Boar and Bear Hunt’ (detail), woven wool tapestry, probably made in Arras, France, or Tournai, Belgium, 1425-30. V&A Museum no. T.204-1957.

Imaging the social reality behind the making of such embroidered clothes – a reality involving girls and women learning this professional skill – allows us to find in the poem another kind of female ‘authorship’ and an activity other than marriage through which adolescent girls could develop their adult identities.

It’s often hard to know who read medieval manuscripts, and that’s certainly the case with the manuscripts in which this poem is found. What we do know is that whole families (including apprentices!) would have gathered around to listen to poems and stories read aloud, preferring this to solitary reading. And we have many manuscripts whose contents cater to the needs of a whole family, children learning their letters to adults. One of the manuscripts of The Assembly of Ladies was made by a scribe working in London in the second half of the fifteenth century. We don’t know his name, or who exactly he made this manuscript for, but we do know that he had professional links to one of the most prominent London families involved in the textile trade: Thomas Cooke, draper (and a mayor of London in his day) and his wife, the daughter of another draper.

I’ve no hard evidence to suggest that The Assembly of Ladies was actually written, or read, as a coming-of-age narrative for girls growing up as apprentices in the London cloth trade. But, simply acknowledging the existence of young girls learning professional skills like this can shape our reading of the poem, and of girls’ place in medieval culture as a whole. Instead of picturing female children as economically passive, interested in clothes as consumers, we can recognise that some of them would have been learning to make professional judgements, to see the world with perspectives gained through the acquisition of professional skill. Without solving the question of whether The Assembly of Ladies was itself written by a woman, we can acknowledge women as authors of their own identities within the poem, as writers of the mottos sewn into their sleeves. And we can acknowledge real medieval girls as active participants in their culture, making an economic contribution.

Note

For this post I drew on Barbara Hanawalt’s work on medieval childhood, and on female apprentices – especially her book The Wealth of Wives: Women, Law and Economy in Late Medieval London (Oxford: OUP, 2007), but also Growing up in Medieval London (Oxford: OUP, 1993).

For the poem, see The Assembly of Ladies in The Floure and the Leafe, The Assemblie of Ladies, and The Isle of Ladies, edited by Derek Pearsall (Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1990).

For the scribe who wrote the London manuscript of the poem (he’s known as the ‘Hammond scribe’), see Linne R. Mooney, ‘Vernacular Literary Manuscripts and their Scribes,’ in The Production of Books in England, 1350-1500, edited by Alexandra Gillespie and Daniel Wakelin (Cambridge: CUP, 2011), pp. 192-211.

Update

As my friend has just pointed out (with a polite lack of ‘duh, you twit’), what the woman with the giant sparrow-hen is carrying is a distaff, not a spindle. Yes, I would make a terrible medieval woman.