The image above comes from a manuscript made in the late fourteenth century. The company of the French king, Charles V, sit at a lavish dining table as they watch a re-enactment of the Crusades – complete with an impressive prop ship captained by the legendary hero Godfrey de Bouillon:

A ship with masts, sails and rigging was seen first; she had for colours the arms of the city of Jerusalem: Godfrey de Bouillon appeared on deck, accompanied by several knights armed cap-a-pee: the ship advanced into the middle of the hall, without the machine which moved it being perceptible. Then the city of Jerusalem appeared, with all its towers lined with Saracens. The Ship approached the city: the Christians landed, and began the assault; the besieged made good defence; several scaling-ladders were thrown down; but at length the city was taken.

This interlude brings together jingoistic nationalism with the celebrations of the feast. The association between celebratory food and the triumphal caricaturing of a subdued foreign enemy may seem strange, but it’s deeply rooted in medieval culture. Feasts were filled with symbols of status and hierarchy, with reminders of wealth and dominance. Nicola McDonald writes about the way a medieval delicacy known as ‘the Turk’s head’ – a pie made to resemble a dark-skinned, long-haired man’s head with a luridly coloured filling, and flavoured with cloves, pepper, sugar and pistachio – reflects the same dehumanising attitudes towards ‘exotic’ foreign enemies that we find in the Crusader romances of the period.

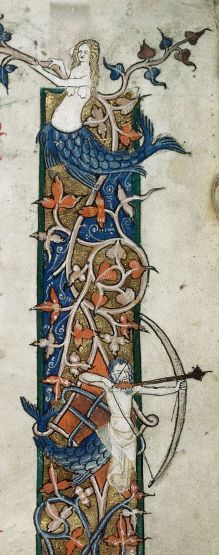

A Saracen or Ethiopian Crusader battles a Sea-Monster in a Fourteenth-Century Prayerbook

For kings – but also, increasingly through the medieval period, for prosperous people much further down the social scale – images of exotic foreignness went hand in hand with the luxury items for the table. As Charles V and his companions watched their interlude, they ate food flavoured with spices brought in on the same sea routes the Crusaders had followed in reverse.

Medieval manuscripts are filled with recipies for ginger, for saffron, for cinnamon and mace. By the fifteenth century, we find recipes mentioning not only the spices, but also a new ingredient – sugar – and a play performed around 1500 has a character describe the exotic cargo of his merchant ships: ‘Spycis I hawe..In my shyppes..Gyngere, lycoresse and cannyngale’ (‘Spices I have … in my ships … ginger, liquorice, and galingale’). In the same year, the cosmopolitan text Information for Pilgrims to the Holy Land foreshadowed a hundred foodie blogs in conflating quality of ingredients with obscurity of their source, advising: ‘Of peres..suche other comfytes, the further ye gone the better shall ye fynde, as well as grene gyngere’ (‘As concerns pears … and other such preserves, the further you travel the better quality you’ll find, and the same with green ginger’). These spices serve as metonyms for the geographies from which they come, representing the wide reach of English and French trading ships and the prosperity that enabled Western European nations to import their cargoes.

Recipies blend with medical remedies, with spices featuring in both. In one textbook on surgery, in a fourteenth-century manuscript, we find the recommendation to give patients ‘fleisch..sauerid with swete spicerie, as canel, gynger’ (‘meat … seethed in sweet spices, such as cinnamon, ginger’); in another, copied in the fifteenth century by Yorkshireman Robert Thornton, the list of ‘spices þat are hate: gynger, longe pepir, white pepir, aloes epotik’ (‘spices that are heating: ginger, long pepper, white pepper, liver-coloured [hepatic] aloes’).

Some concoctions sound fairly unpleasant to modern readers – in the 1325, we find instructions for cooking pike or turbot with almond milk, spices, saffron and sugar – though others sound more familiar, such as the ‘good hypocras’ made of wine and spices – mulled wine – recommended by John Lydgate in the fifteenth century. In the Middle English romance Reinbrun, found in the London Auchinleck manuscript of the 1330s, we hear of merchants bringing expensive and varied stocks including spices:

Gingiuer and galingale,

Clowes, quibibes, gren de Paris,

Pyper, and comyn, and swet anis;

…

Fykes, reisyn, dates,

Almaund, rys, pomme-garnates,

Kanel and setewale …

(Ginger and galingale,

Cloves, cubeb [pepper], grains of Paradise,

Peper, and cumin, and sweet anise;

…

Figs, raisins, dates,

Almond, rice, pomegranates,

Cinnamon and turmeric … )

These spices were popular – luxury items, certainly, but in the category of luxuries affordable to quite a lot of reasonably well-to-do people, and as a treat, to more. Official documents relating to legal weights and measures give an intriguing insight, recording that ‘warys that be sold by the lb., as peper, saffryn, clowys, mace, gynger and suche other..be called Sotyll Warys’ (‘goods that are sold by the pound, as pepper, saffron, cloves, mace, ginger and such others … are called Subtle Wares’). The term ‘subtle’ suggests refined luxury, but the idea of buying a pound of ginger – let alone saffron – would be beyond most keen cooks’ budgets today.

Comparative lists, giving the prices of various items – some luxuries, some common purchases – bear out the (relative) availability of spices. In a letter of 1471, one member of the Paston family writes to another, off on business, asking ‘sende me word qwat price a li. of peppyr, clowys, masis, gingyr, and sinamun’ (‘send me word – what price is a pound of pepper, cloves, mace, ginger, and cinnamon?’). As early as the thirteenth century, we find surnames redolent of the spice trade: Roger Spice, William Gingerer, Simon Pepperwhite.

The rich fragrance of spices, and their appealing colours and shapes, lent themselves to imaginative imagery, much of it drawn from the Old Testament. Wycliffe’s Bible translates the ornate lists of spices and aromatics in the Song of Songs into English as ‘fruytis of applis, cipre trees, with narde; narde, and saffrun, an erbe cleipid fistula, and canel, with alle trees of the Liban, myrre, and aloes, with alle the beste oynementis’ (‘fruits of apples, cypress trees, with nard [incense]; nard, and saffron, a herb called cassia, and cinnamon, with all trees of Lybia, myrrh, and aloes, with all the best ointments’).

The same lyricism, and same profusion of spices, is put to very different, and sadder ends, in the Middle English elegy Pearl, where the speaker laments over his dead daughter’s grave and declares:

That spot of spyses mot nedes sprede

Ther such ryches to rot is runne:

Blomes blayke and blwe and rede

Ther schyne ful schyr agayn the sunne.

(‘That spot must spread with spice-plants,

Where such richness has run to rot,

Blossoms yellow and blue and red

Must shine there, clear, against the sun.’)

As this lament reminds us – like the familiar imagery of the myrrh brought to the baby Jesus and foreshadowing his death – spices are also associated with the colder side of religious life. The preparation of spices for medicine gives rise to more monitory and penitential metaphors, such as this description of penitence, found in the didactic Book to a Mother:

Þe soule..pouneþ in a morter of hure conscience monye and diuerse bitter spices of hure synnes.

(‘The soul … pounds in the mortar of her conscience many and diverse bitter spices of her sins.’)

‘Thiese serpentes … with white peper theym feden.’

Spice suggests both sanctity and penitence, both sweet taste and bitter medicine, the mingled attraction and danger of the exotic. A (fictional) letter from the great conqueror Alexander claims that dragons – serpents – fed on white pepper. In Cynthia Harnett’s children’s novel A Load of Unicorn, the ringleaders of a Lancastrian plot against the Yorkist king Edward IV use a quick-witted Cockney spice-peddlar as go-between, and his seemingly innocent tallies of wares conceal a careful scheme to record covert sympathisers to the cause: “I’ll put them down as peppercorns in my list of spices.”

The same link between spices and enemy threat crops up in Mummers’ Plays, which were recorded in versions from the medieval period onwards. There are several versions of the St George Mummer’s play – one here – and it makes use of the stock characters of medieval interludes and romances: St George, the enemy Turkish knight, the King of Egypt’s beautiful daughter. Early versions give St George a jingling rhymed challenge in defiance of the Turkish knight:

“I’ll slash him and stab him as small as the flies!

And send him to the cookshop to make mincepies!”

Later on, the homely English ‘cookshop’ is replaced with a more exotic location. In 1899, we hear:

“I’ll hack him up as small as dust,

And send him to Jamaica,

To be made into mince-pie crust!”

Here, ‘Jamaica’ probably functions not so much as a ‘real place’ as it does as a generalised symbol of the exotic, a mingled image of racial alterity and of the sugar and spices of mincemeat. Yet the racist undertone is pointed up by a third alternative, which has the valiant St George vow to send his Turkish adversary ‘to Satan, to make his mincepies!’.

Charles Causley’s brilliantly chilling Christmas poem ‘Innocent’s Song’ – which gives the Coventry Carol a run for its money – exploits the same imagery, with its description of the evil King Herod as a ‘smiling stranger/ With hair as white as gin’. Echoing the medieval ‘Saracen’s Head’ delicacy, or the Mummer’s Play with its Turkish knight chopped into spiced mince-meat, Causley’s poem transforms the human figure into a concoction from the medieval kitchen:

Why does he ferry my fireside

As a spider on a thread,

His fingers made of fuses

And his tongue of gingerbread?

Why does the world before him

Melt in a million suns,

Why do his yellow, yearning eyes

Burn like saffron buns?

The image, like the earlier texts, turns a once-real threat of danger into something both more exotic, and more palatable. The texts exoticise and parody images of foreignness in a way that makes us uncomfortable, linking to a disturbingly long tradition of caricatured, indeterminate foreign Others – Saracen, Turkish, Jamaican, Ethiopian; they also draw on the seductive scents and tastes of spices to cover up – like rotten meat – the unsavoury hints of nationalistic propaganda lurking beneath.

But, there is another side to this coin. The images and anecdotes, recipes and remedies and lists of prices for spices here prove to us that medieval English men and women were not cut off from a world of cultural – and racial – difference. Even ingredients we tend not to expect in medieval cooking – sugar, for example, or cubeb peppers, cumin, turmeric – are all there alongside the more traditionally-expected mace, ginger and cinnamon. In the same way, these texts and images are part of a wider reminder that medieval England – and medieval Europe – were not unvaryingly white spaces. The Medieval People of Color project – which I’ve mentioned before, and which regularly receives abusive comments for its excellent work uncovering the histories and images of medieval people of color – gives a fascinating and complex picture.

It’s hard to guess at what ordinary medieval people – of whatever skin colour – thought of the images around them, or of the geographies evoked by the spices that passed through their kitchens. But we can at least look at this history and acknowledge it, think about it, work its images of strangeness and familiarity into our understanding of the medieval past.

Happy Christmas!

With thanks to Ruth Allen for the St George Mummers’ Play, Sjoerd Levelt for the baby dragon in the margin of BnF Latin 919, and Emma Goss for food styling.

References:

Food History Almanac, Vol 1, ed. Janet Clarkson (2014)

Peter Millington, ‘Textual Analysis of English Quack Doctor Plays: Some New Discoveries’, Folk Drama Studies Today (2003), 97-132.

Nicola McDonald, ‘Eating People and the Alimentary Logic of Richard Coeur de Lion,’ in Pulp Fictions of Medieval England: Essays in Popular Romance (Manchester: University Press, 2003), pp. 124-150.

Images in this post are taken from Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. Ms. fr. 2813; London, British Library, Add MS 4213o; Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Manuscrits, Latin 919; Musée du Petit-Palais L.Dut.456 and London, British Library, Royal MS 10.

The medical textbooks are to be found respectively in Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Ashmole 1396 and Lincoln, Cathedral Library MS 91. The play with the spice-merchant’s ships is found in the Croxton Play of the Sacrament, in Dublin, Trinity College MS 652. The Information for Pilgrims to the Holy Land is found in London, British Library, Cotton Appendix 8. The Book to a Mother is found in Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 416.