I’ve just finished watching a BBC programme with the title ‘A Very British Renaissance‘. Now, I admit I was expecting to have some strong reactions to this, since I came to it from the brilliant scholar David Rundle’s blog, where he’s just written a learned and funny take-down of some of the annoying assumptions therein. As he points out, this programme was dead keen to push an image of a ‘distinctively English’ period of history, during which we Brits left our insular isolation behind and began to beat the Continent at its own game. The emerging British (= English) Renaissance was a time of genius and beauty, so narrator Dr James Fox argues, an amazing advance on the benighted, crude and murky culture of the Middle Ages. It was also, I began to realize, yet another Age Without Women.

The focus of my irritation in this post is evenly split between bad history, and dubious revisionist misogyny, so you’ll have to excuse a little back-and-forth between the two. We’ll take the first point first. People do often assume medieval England was completely cut off from the rest of the world. I’m not sure why, seeing as most people are dimly aware that the English crown owned parts of France, but there we are. I always find it interesting that people assume there were, for example, no non-white people in medieval England, and just as soon as I can afford this gorgeous-looking book, I’m going to buy it. On a more domestic level, if you read medieval recipes you’ll soon notice how many contain ingredients – ginger or saffron, pepper, oranges or almonds, for example – that remind you people had access through trade routes to distant places.

Studying medieval manuscripts, you can really get a sense of how much even quite ordinary people moved around. At the moment, I’m looking at some thirteenth-century romances and fabliaux (rude stories, if you’re interested) in a manuscript made in France. By the fifteenth century, it had been brought to Britain, and ended up in the hands of a family of East Midlands gentry – hardly the sort of people you might expect to be reading exciting foreign books. But they did.

Similarly, the British Library has just digitized what they’re telling us is the ‘first English autobiography’ – though this simplifies a phenomenally complicated story which is partly autobiography, partly dramatization – written by a Norfolk woman called Margery Kempe. She wasn’t particularly rich or socially important, but she made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem via Venice and Rome, and once she was back home she briefly employed an amenuesis (she couldn’t write) who was married to a German woman.

These are just examples from off the top of my head, to show that, actually, medieval England was full of people coming and going from the Continent – and you’ll notice we’re not just looking at men, or the aristocracy, but at relatively ‘ordinary’ men and women.

So … on to the second point, the argument that medieval England was a land of mud, muck and ignorance in which happiness consisted of not catching the Black Death and the highest ambition of every peasant was to own his own turnip. I’m pretty easy to wind up on this issue, because I really hate the connotations the word ‘medieval’ carries to a lot of modern writers. You read an article about women being oppressed, or creativity stifled, and nine times out of ten the author will refer disparagingly to ‘medieval’ attitudes. So, I had my agenda polished up from the start.

The programme begins with sunlit shots of Italian Renaissance sculpture, before cutting to a scene of Dr James Fox narrating as he trudges through squelchy English mud, which he compared (no, really) to the medieval period. His voiceover was all soaring phrases and triadic alliterations (which, you know, made me think of medieval poems like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight or Pearl … but who’s checking?), as he attributed to the English Renaissance a sparkling constellation of brilliant developments. There were our ‘first’ great paintings, our ‘first’ scientific breakthroughs, and our ‘greatest writer’.

Shakespeare, of course. The Chandos portrait. In which the earring certainly doesn’t signify he was gay, ohno. There was no gayness in this programme! It didn’t exist before 1967, doncha know?

All of this began, so Dr Fox explains, in 1507, when an Italian artist called Torregiano left Italy under a cloud, after losing his temper and punching Michaelangelo in the nose. I was particularly sad to see no homoerotic undertones were detected, probably because my mind is in the gutter with the ‘medieval mud’. Anyway, after this Clarksonesque bust-up Torregiano emigrated to

“Europe’s most philistine backwater … England. When Torregiano reached England, it must have felt like he’d stepped back into the past. The Renaissance had been raging in Italy for almost 200 years, but here there was absolutely no sign of it whatsoever. … The British hadn’t had time for a Renaissance. They hadn’t even had time for art.”

Dr Fox claims, with a stern frown, that medieval England ‘didn’t even have a word for painting’. I’ve used up my weekly allowance of Patrick Stewart facepalms, but you can imagine my reaction. The Middle English word for painting is, well, uh … painting. To be precise, peinture. Minor irritations like this didn’t stop me noticing that, by this stage in the narrative, we’d heard the phrase ‘craftsmen,’ used to describe medieval artists, about a dozen times. You know, because women never got in on this activity.

Unknown Artist from Giovanni Boccaccio, Des cléres et nobles femmes, Spencer Collection MS. 33, f. 37v, French, c. 1470. From this site, which is worth a look.

Certainly, I couldn’t help noticing that this was a highly masculinized world we were being shown. We moved from the nice macho nose-punch that set the English Renaissance in motion, through a line-up of eminent men: Holbein, Nicholas Kratzer (he of the ‘genuinely Renaissance mind’), John Damien, Thomas Wyatt and Thomas Tallis. Wyatt is credited, here, with introducing love poetry in the Petrarchan tradition to boring old England, which had seen no literature since Chaucer.

(That high-pitched noise you hear is the steam emitting from my ears.)

Wyatt went off to Italy, learned to write sonnets, and came back to Henry VIII’s court to immortalise anonymous women. Keen to stress the intimate, soulful nature of Wyatt’s writing (privacy is, I notice, also a hallmark of the ‘Renaissance’ superiority, in a neat line to the Romantics’ male-dominated ‘lonely genius’ idea), Fox intones:

“Wyatt’s poems were written by hand …”

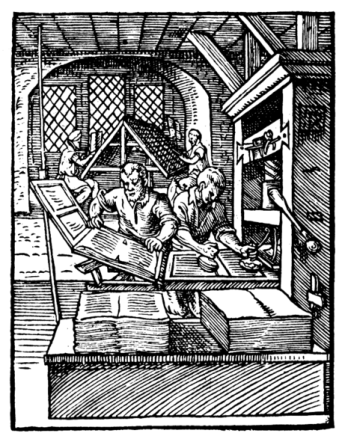

You know, I really thought he’d rise to a laptop. Or if you are less of a realist philistine than I am, perhaps you can imagine the great man sitting down to a printing press and composing away.

Now, I love Wyatt’s poetry, especially ‘Whoso list to hunt‘. But – leaving aside the fact that the trope of young men going out into the forest to discover true love is straight out of the medieval romance Fox dismisses – these poems are predicated on a particular view of the relationships between men and women which – how can I put this? – does come across as just slightly objectifying. Just a tad. Cos, you know, representing a woman as a deer to be shot is one of those romantic gestures of which you can imagine Edward Cullen approving.

In Fox’s version of events, then, the English literary Renaissance began with writing in which women were objects, and this was a vast improvement on such ‘muddy’ medieval texts as Kempe’s bizarrely brilliant ‘autobiography,’ the lyrical mysticism of Julian of Norwich, the fantastic cross-dressing romances like the Roman de Silence, or the elegantly playful Assembly of Ladies, which I wrote about a few weeks ago.

We were well into the territory of the ‘Great Literary Tradition’ by this point, though, and that tradition doesn’t have room for most of the literature that gives screen time – or even a voice – to women. Still commenting on Wyatt, Fox’s colleague claimed that Wyatt’s coy description of a romantic encounter was an amazing first in the history of writing about sex:

“nobody in medieval poetry went to bed with anybody, only in dreams, that’s why this is such a radical poem.”

I’m not quite sure what was happening in Chaucer’s Miller’s Tale if no-one in medieval poetry went to bed with each other*, for the tale describes the adulterous couple’s tryst in pretty blunt terms:

“Doun of the laddre stalketh Nicholay

And Alisoun ful softe adoun she spedde.

Withouten wordes mo they goon to bedde.”

(‘Down the ladder sneaks Nicholas/ And Alison, very quietly, hurried down. Without a word more they go to bed.’ Chaucer, Miller’s Tale, ll. 540-42.)

I’d also like to share with you a poem which you won’t be surprised to learn is one of my favourite examples of unsubtle punning, which begins with the auspicious line ‘I have a gentil cok’. The poem goes on to ennumerate the virtues of this wonderful bird, concluding ‘And every night he perches him/ In my lady’s chamber’.

Perhaps Dr Fox and co. were plagued by innocence?

If you read my blog regularly, these poems will not come as a huge surprise, given what we know of medieval illumination. So I’ll take the opportunity to share this image, illustrating the Roman de la Rose, by Jeanne de Montbaston – just as a reminder that women were sometimes at the creative helm:

And there’s always the wonderful Talbot Shrewsbury book, comissioned to celebrate the marriage of Margaret of Anjou to Henry VI, with this image of the conception of Alexander the Great, which I like to caption ‘In bed with my dragon’:

There’s a reason the programme didn’t acknowledge the existence of the bawdy story I quoted, or the images I’ve shown. What we’re looking at is canonization, the process whereby certain cultural products are deemed to be self-evidently superior to others, worthy of study and attention. In this programme, the canon of medieval literature was rewritten, to include Chaucer (though a reading of Chaucer which excluded the low-status Miller’s Tale), and to exclude fifteenth-century romances, the Humanist writings that testify to the culture of intellectual exchange between England and the Continent, and the multitude of texts I write about, in which women are authors and protagonists, businesswomen as well as aristocratic ladies, thinkers and doers, and not simply mute sexual objects.

By excluding a lot of medieval culture, this programme is able to draw a straight line from Chaucer to Wyatt to Shakespeare to the Romantic Poets, whose notion of solitary (male) genius was never far from the subtext. It’s not a big leap from this, to the idea that Great Literature, or Artistic Genius, or whatever amazing idea you want to mention, is really something that all intelligent men have been able to recognize throughout history. It’s something the truly brilliant just understand, and the fact that there are no women in this picture is really not anyone’s fault: it’s just how History is.

I’ll stick to my medieval mud, thanks.

Note:

Please excuse typos – it’s the end of a very long week!

* Update

Being – as I am – ever keen to back up my arguments on this blog with the most rigorous scholarly research (actually, there is a lot of rigorous scholarly research going on in the background, I promise), I return with this comment on medieval beds and their usage. Hollie Morgan, specialist in medieval beds, opines:

“hahahahahahahaha. It’s all about sex. And beds.”

But is too tired trying to finish her PhD to comment more about it. But when it’s done, Dr. Fox is welcome to read 100,000 words on muddy medievals in bed.

In all seriousness, her PhD project constantly challenges me to think more precisely about our assumptions concerning the medieval period, and she’s helped me to express something I found unsettling about this programme: throughout it, High Art was described as if it were entirely separate from daily life. I don’t think we’ll ever get a satisfying picture of fifteenth- or sixteenth-century England like that.