This post is in the nature of an exorcism. I’ve gone back and forth about writing it far too many times. I’ve worried it’d sound trivial or whiny (or both!). But, although I left full-time academia nearly two years ago, in the winter of 2021, I still haven’t quite set it to rest. Very nice people I know assume I left academia because it was toxic, or because I didn’t enjoy it, and that isn’t the case.

I loved working in academia. I started writing this blog in 2013, when I’d just finished my PhD, and straightaway I found a wonderful community of scholars who were just as fascinated as I was by the brilliant, delightful weirdness of medieval literature. I found the medieval ‘queerdievalists,’ and it wouldn’t be a total exaggeration to say that I found the courage to come out (again, after years of struggling) because LGBT academics gave me such a generous, inclusive sense that I might have somewhere to belong. Writing this blog brought me into contact with almost all of the people I’ve ended up publishing with. It gave me the space and the confidence to test out the ideas that ultimately became my first book. And it helped me develop my ideas for lectures when, in 2014, I started a two-year job in the English Faculty at Cambridge. That job led to more teaching at Cambridge, and by the time I left Cambridge in 2018, I’d been working for a year as a Director of Studies at Newnham College, Cambridge. I worked hard for those jobs. When I look back at my old blog posts, I can feel the excitement I felt then. I can remember the absolute delight of giving a lecture and seeing students catch the bug for Piers Plowman or medieval romance or whatever else it might be. I can remember the huge, heart-lifting sense of optimism and gratitude I associated with academia.

I still felt like that in 2018, when we moved away from Cambridge and I took time out to look after our baby daughter. Then, in 2019, I started a postdoc fellowship that was to run for two years. It was quite a prestigious, competitive fellowship; it came with a large grant, which I’d won by proposing a study I was absolutely passionate about. I started with the thought that there are lots of studies of medieval maternity: motherhood is the one role we all (still) expect of women. But what about all the women who never became pregnant – or who became pregnant and lost their babies, before or during labour? I wanted to study these never-mother women, to understand how they (and their families) grieved for children who never were. We’re often told that, in the past, death was so common that no one mourned a dead baby; women who experience miscarriages are often made to feel they are being over-sensitive in feeling sad. It’s nature’s way. In the past, you’d never even have thought about it. I had found enough medieval evidence to indicate that this was very, very wrong: but I wanted to find out more, and to share it: to find a way to make bereaved parents feel less cut off from history.

I thought it was an important project, but one of the really difficult things about academia is figuring out whether you’re any good. We all have imposter syndrome and we all spend our time writing applications and grants where we have to grandstand about how amazing we are: the combination is apt to cause confusion. But the feedback from my postdoc grant awarding body was encouraging. They described my publication record – papers in leading journals; a book due for publication – as impressive; they liked my extensive teaching experience and public engagement. They liked the project, too, and agreed that it was an important, timely idea. They explained that they expected this postdoc to take my career to the next level. When I read that report I felt so proud of the work I’d done in the 5 years since I finished my PhD.

From the first moment I set foot in the department, I felt as if all of that work, and all of the past five years, had been wiped out. Everyone I met – faculty, students, other postdocs – treated me as a new PhD student. Repeatedly, I’d explain, and repeatedly, they’d repeat ‘so … what are you hoping to write your PhD on?’ (Or, ‘are you PhD or MA?’). A fellow postdoc, recently graduated, offered to take me for coffee, and burst into incredulous laughter when I referred to myself as an employee. Another postdoc mentioned the existence of a fellows’ common room, but looked at me suspiciously and turned away when I asked where I might find it. I had a desk in a shared office, but to print anything I was told to go into the PhD workroom. Early on, I tried to make friends with the rest of the department, suggesting we meet up for coffee, but was met with startled looks and shrugs. I started to realise that the laughter, the incredulity, the ridicule, was performative. There were almost no women in the department, and they weren’t welcome.

Even so, I genuinely wondered whether I had, inadvertently, applied for a position that was somehow equivalent to a PhD studentship. In my new department, postgraduate students gave regular presentations at the weekly research seminar, alternating with faculty and invited speakers. Permanent faculty often missed the student presentations; when it was my turn to speak, no permanent staff member except my mentor attended. A student grimaced throughout the talk and shook his head visibly, then explained afterwards that he was shocked by my research into women’s reproductive history, and considered it ‘a bit much’. The second time it was my turn to give a paper, the head of department attended … and pointedly questioned my citations (60:40 male/female). ‘Why do you only cite women?’ As he glazed over listening to my answer, I realised it wasn’t really a question. Afterwards, the postdoc who had taken me for coffee on my first day discovered I had a book in press, and loudly ridiculed me, repeatedly telling senior colleagues it was ‘ridiculous’ I’d been considered for publication. To add to all the fun, there was constant low-level homophobia (‘oh … you are not the biological mother but you took time out with your daughter? I didn’t realise that’ … ‘isn’t it strange you work on lesbians and on motherhood?’). I can’t begin to talk about what happened with teaching and with finances.

It’s hard to convey the impact of constant, drip-drip-drip comments. When I write them down, they don’t seem terribly wounding, and I can’t imagine I’d have been upset to be mistaken for a student if it’d only happened once or twice. But, working on a topic that was all about women being told they couldn’t trust their emotions turned this into a perfect storm. Since then, I froze when I needed to reply to things. I found it difficult, then impossible, to write. I still do.

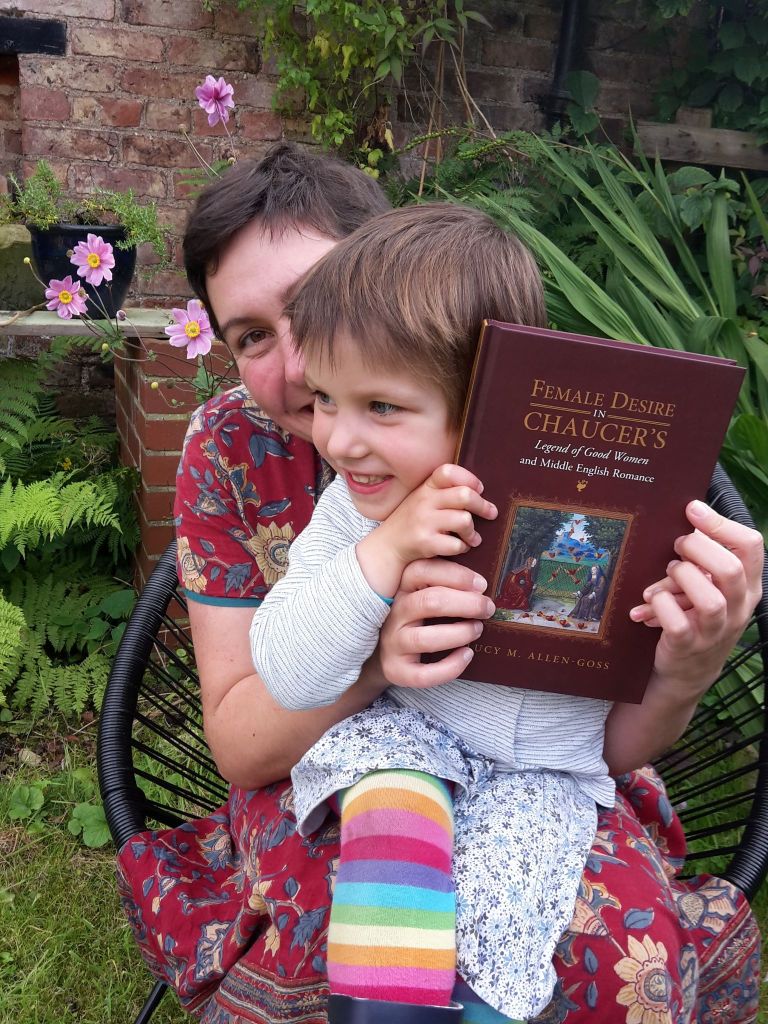

On balance, I can see that the reviewers who said nice things about my postdoc proposal weren’t wrong. Since then, my book has been published and it’s done well; I was really excited by the academic reviews and even more excited that it made it to the Times Literary Supplement. I really wanted to reach readers outside universities, so that was important to me. During the pandemic, I enjoyed becoming part of the Lives in Medicine team at the University of Oxford, and I’m really proud of the public engagement talks I’ve given about my research into pregnancy loss.

I think this may be the last post on this blog, so I want it to end with something good. Very often, we read that academia is toxic. But, having worked in a genuinely toxic department, I think there are a lot of healthy, vibrant spaces in academia. There are so many senior colleagues who work to lift up junior scholars; there are so many teachers who push to get the best for their students.

I truly think we are working to make things better, and I think it’s work we should all be proud to do.