At Cambridge, if you study English, you sit two compulsory final exams: one in Tragedy, and one in Practical Criticism, which is close reading of a selection of texts and extracts. On the spur of the moment, you have to work out how to take the text to pieces, and how to put it back together again in some form of coherent argument. I can’t honestly remember very much about my own Prac Crit exam, except that it over four hours long, it was a very hot summer and the room where I was taking my exam had malfunctioning heating, which couldn’t be switched off. But I was reminded of it the other day, as we discussed why this exam can seem so intimidating.

I know lots of people I know claim that doing English Literature ‘ruined’ books for them, that taking a book to pieces as you do when you’re doing close reading spoils it. The original idea of Practical Criticism – as it was developed by critics in the early twentieth century – was that students should learn to read texts without knowing the most basic details about them, such as the name of the author (and therefore, his or her gender) or the date he or she was writing. In theory, this should be freeing. It’s quite close to the anti-hierarchical aims of Feminist Pedagogy. And yet, it is still intimidating, and that sense that something has been pulled to pieces and laid bare can, I think, relate as much to us as readers, as to the texts we read. In short, you can feel very exposed doing close reading.

I love close reading (and I’ve done a bit of close reading in this post, largely as an antidote to writers’ block). But, as I did it, it occurred to me how difficult it is to untangle questions of gender and exclusion from English Literature, even when we think we’ve stripped back texts to their most basic, unmediated forms. So I thought I’d share what I was thinking.

This post also gives me the chance to link to this lovely piece about Tudor falconry, because, as you might guess from the image above, this post is partly about hawks. The other night, I went to a book talk in Heffers in Cambridge, because I wanted to see Helen MacDonald talk about her book H is for Hawk, which I read just before Christmas and which I’ve mentioned on here before. With her were David Cobham and Bruce Pearson, who wrote and did the images for The Sparrowhawk’s Lament. I’ve not read it (and I really want to now), but the book charts the state of British birds of prey, many of which are in very low numbers. MacDonald asked Cobham how he’d come to the title for his book, and he replied that it comes from a medieval poem, which he’d read in hospital while waiting for a serious operation.

Obviously, I pricked up my ears. It turns out that the poem he titles ‘The Sparrowhawk’s Lament’ is one of the many medieval lyrics that use the Latin refrain ‘Timor mortis conturbat me’ – ‘The fear of death troubles me’.

As Cobham was being anesthetised, so he says, he thought he heard the ring of an Angelus bell, and the sound of a choir singing the Latin line – which is, of course, from the medieval Office of the Dead. This eerie anecdote made me think about the poem, and so I sat down to do some close reading on it. I’ve not pulled it together, but just left it as a sequence of comments to show you how I read the poem.

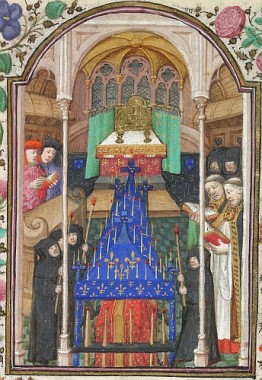

The burial of the dead (from the Office of the Dead). London, BL MS Yates Thompson 3, f. 211r.

The poem like this:

In what state that ever I be,

Timor mortis conturbat me.

As I me walked in one mornynge

I hard a bride both wepe and synge; bride=bird

This was the tenor of hir talkynge – substance of its reply

Timor mortis conturbat me.

I asked this bride what he mente.

He said “I am a musket gente. musket=male sparrowhawk

For dred of deth I am nygh shent: nygh shent= nearly destroyed

Timor mortis conturbat me.

Jhesu Cryst, whan he shuld deye,

To his Fader lowde gan crye. gan crye = cried out

‘Fader, he seyde, ‘in trynyte,

Timor mortis conturbat me’.”

Whan I shal deye I knowe no day

Therefore this song synge I may

What contree or place can I not seye

Timor mortis conturbat me.

I really love the language here. The Latin phrase itself is beautifut. ‘Conturbat’ suggests disturbed motion. The verb ‘turbare’ means ‘unsettle’ or ‘disturb’ all on its own (it’s related to words like ‘turbulence’ and, I think, ‘tornado’), and the prefix ‘con’ intensifies that sense, so that you have a cumulative effect of overwhelming, spiralling movement. I think it’s probably what Yeats is getting at with the opening lines of The Second Coming: “Turning and turning in the widening gyre/The falcon cannot hear the falconer”.

This evocation of turbulent motion is juxtaposed with the following image of the bird, so that we have a suggestion of the hawk tossed and ruffled from the wind. This is supported by the words the bird itself uses to describe its condition: ‘nigh shent,’ or ‘almost destroyed. This word has three overlapping senses in Middle English: primarily, it refers to the physical state of being injured or hurt, a sense that is strengthened because it rhymes with the word ‘rent,’ meaning ripped or torn apart, and we know from studies carried out in psychology of reading that our brains subconsciously register rhyme words as we read. However, this first meaning of the word gives way to a spiritual meaning of ‘damned’ and a moral sense of ‘shamed’: to be ‘shent’ is to be injured in both body and soul. The line rationalising this injury is mysteriously vague: “For dred of deth I am nygh shent” could refer to the hawk’s own impending death – ie., fear of mortality, which is the usual inteprretation of the Latin line – but in this context of the speech of a bird of prey, a bird whose function is to deliver death, it could also suggest the fear of inflicting mortal wounds, which would explain the mingled fears of shame and damnation.

This reminds me of T. H. White, whose novel The Sword in the Stone echoes this poem and imagines a goshawk half-mad with this fear and guilt, driven to kill whatever comes near it, but tormented by its own murderous impulse. White’s hawk is a real character in his novel, more than a mere personification of the fear of death, speaking – as this hawk does – almost in a human voice. Yet this hawk can also be read as a symbol, and the juxtaposition of the bird of prey with the narrative of Christ’s Crucifixion evokes another parallel, this time to a comparable medieval lyric. The Corpus Christi Carol begins plaintively “The falcon hath borne my mate away …” and the image of the falcon and its prey gives way to the image of a dead knight mourned by his lady, and, finally, to a tombstone that bears the legend “Corpus Christi”: the body of Christ. Here, as in ‘The Sparrowhawk’s Lament,’ the bird of prey foreshadows the death of Christ on the cross. It’s incredibly bleak, this image of Christ pleading on the Cross to his Father, but it gives the familiar, often over-theologised narrative a piercing immediacy: even Christ fears death.

The final stanza of this poem could seem enigmatic, even anti-climatic: instead of offering some kind of comforting resolution of these jumbled images of whirling death, the falcon, and the crucifix, it returns to a first-person speaker meditating on the utter unknowability of death. We can’t even be sure (because medieval texts don’t generally indicate one way or another, although modern punctuation can) whether or not the speaker of the last stanza is still the hawk, or whether it is now the ‘I’ of the opening lines. This anonymity of the speaking voice gives it a loneliness, but also allows it to speak for all of us – it could be anyone’s voice, facing down death.

If you look at what the rhymes are doing in this poem, you’ll see the rhyming tercets of the first two verses (rhymes across three lines, followed by the refrain, timor mortis conturbat me) give way to an imperfectly-rhymed quatrain in the third verse (deye/crye/trynyte/me) that seeks to incorporate the refrain into the rhyme scheme. And, finally, the last verse is a perfectly rhymed quatrain, with the refrain entirely incorporated, as if to still the turbulent movement and spiritual turmoil the line articulates. The Latin line initially jars the rhyme scheme and cannot be reconciled with the English speakers’ thoughts; by the end of the poem, it has become part of the speaker’s own idiom, chiming in with the speaker’s own thoughts.

This is, obviously, a poem about mourning, and a poem about the basic Christian confrontation with death. But, as I read its echoes backwards into the ancient Latin of the liturgy, sideways into the medieval Corpus Christi Carol, and forwards into Yeats and White, I think it’s also a poem about communication. How do we express fears? At what point do we manage to grapple with the language of death in such a way that it becomes part of our own vocabulary? When does the strange speech of the hawk suddenly start to make sense?

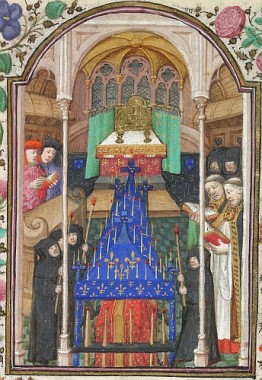

British Library MS Harley 7026, f. 16r (detail)

I know this poem, but not primarily as a medievalist, because in T. H. White’s Sword in the Stone (the story of King Arthur’s childhood), the birds of prey kept in the castle mews sing a version of it. This neatly links Cobham’s and MacDonald’s books, since she talks a lot about White and his writing. The version of the poem I’ve quoted above is from a manuscript written by a grocer, Richard Hill, who lived in London in the late fifteenth century. In fact, I happen to know that the Corpus Christi Carol I quoted above is in the same manuscript, so it’s perhaps no surprise that the two texts echo each other. However, the poem is much older than the late fifteenth century: in a slightly different version, it’s found in the Vernon manuscript, a huge book (it weighs over 2okg), which was copied somewhere in the West Midlands, in the 1390s. So, the poem is at least this old, and might well be even older.

It is difficult not to notice – even before I add the contextual historical information about Richard Hill – that the echoes that readily come to my mind to contextualise this poem, are echoes of male writers’ texts, or (in the case of the Corpus Christ Carol), echoes of texts whose authors are unknown. The gendered speakers of the poem are male, although we do not know the gender of the initial speaker who hears the bird ‘both weep and sing,’ and since women certainly did fly sparrowhawks, there is no strong reason to assume a male speaker. One of the most famous medieval texts on hawking, which lists each bird alongside the person to whose social status it is most appropriate (“… in what state so ever I be …”) is associated with a woman, Dame Juliana Berners. More persuasively, the Corpus Christi Carol, which maps the same image of the falcon and the dying Christ onto a love story, a story of the bird’s lost mate and the lady mourning her lover, might prompt us to hear a female speaker. Like the hawk that both weeps and sings, the lady of that poem “weepth both night and day“.

In the earlier version of this poem, the version written sometime in the fourteenth century, the pronouns used to refer to the sparrowhawk are less settled than they are in this later version. In the version I quote, the hawk is a male, a ‘musket,’ and is ‘he’ (I promise I looked carefully at the manuscript, and though it’s swirly handwriting, it’s definitely ‘he’). But in the earlier version, the hawk is ‘she,’ although still a ‘musket,’ presumably because hawks (like ships or bells) are often ‘she’ even when given male names. Once we recover these facts, the significance of that ‘anonymous’ voice in the final lines comes clearer – to me, anyway. The speaker is not gendered, but – like hawks, ships and bells – anonymous speakers throughout English Literature are often, in Virginia Woolf’s words, women. Finally, Helen MacDonald points out that hawking itself is a gendered business, with hawks imagined as women to be courted, romantic partners like the mournful lady in the Corpus Christi Carol.

To recover female voices within such a male-dominated poem – and within such a male-dominated textual tradition, with its echoes of Yeats and White, the clerics of the medieval Church and the Father and Son of the Trinity – is difficult, and daunting. As is fairly often the case, it requires more contextual knowledge to find the echoes of women’s voices in this poem. This is because close reading is never really close reading in perfect isolation from the hierarchical structures of English literary culture – as the first proponents of Cambridge Practical Criticism thought it could be. It’s a tool we use, not an ideology. But, at the same time, we can’t forget that, studying hundreds of years of male-dominated literature and literary criticism, it’s a tool that can’t be separated from the ideological conditions in which it was developed.

Note

I wrote this in the middle of 1) horrible writers’ block and 2) lurgy, so please be gentle. It’s Cambridge-focussed, but the basic question – how do we learn to read literature, and can the tools we use ever be free of gender bias – is pretty relevant to all of us, I think.