I’ve spent a lot of time so far looking at medieval images and texts – and records – that show how medieval misogyny shaped women’s lives, and how modern attitudes towards women’s bodies and women’s testimonies are embedded in this long history. There are more positive stories. I’ve suggested that Jeanne de Montbaston, the artist who produced the subversive and witty pictorial responses to the misogyny of the Romance of the Rose as she illustrated it, is one example. So, to find more, I went to look at more medieval artists and their work.

In medieval literature, virtues such as truth, wisdom and reason are often personified, and when they are, they are almost invariably pictured as women: Lady Truth, Lady Reason, gracious figures who act as teachers and guides.

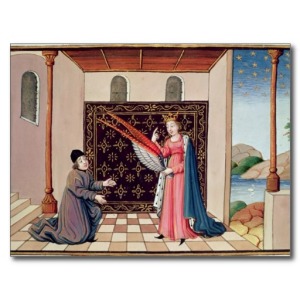

In this image, for example, the author Boethius is pictured kneeling humbly before the crowned figure of Lady Philosophy, who offers him wings.

This isn’t so strikingly woman-friendly as it first appears. Images like this give women the appearance of status, but only the appearance. In effect, despite the humble postures of the male authors, the message is that these men have personified virtues – Truth, Wisdom, Philosophy – dancing attendance on them as they busy themselves with the important work of creating literature. Typically, the conversation follows the conventions of a romance – the male author treating his lady as a lover and trying to please her.

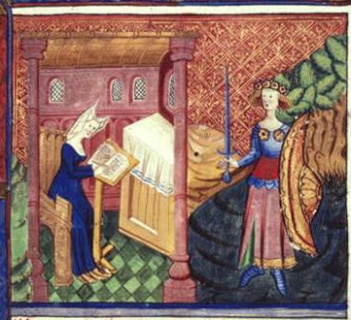

Here’s an image of Jean de Meun, author of the Romance of the Rose, looking suitably engrossed in his writing as his lady stands by with books for inspiration.

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS Fr. 1728. I like to imagine Jean is thinking ‘darn, why can’t real women be more like the ones in my head?!’

However, although this image pictures Christine herself as dispenser of wisdom, the book also features an actual personification of Wisdom, like those in the books of her male peers.

This image shows Christine, sitting at her desk in the same blue dress, while Minerva (goddess of Wisdom) stands beside her, carrying her sword and shield of truth. In this, the image resembles those of male authors. But because Christine is female, her artists were able to draw on a whole new set of connotations that are not evoked by male author portraits. So here, Christine sitting at her desk with her books resembles none other than the Virgin Mary, who was always pictured sitting with her prayer books at the moment when the Angel Gabriel came to tell her she was to bear God’s son.

Christine’s book, then, takes the established iconography of the male author and enriches it with feminine imagery. In presenting two female figures – Minerva and Christine – the artist also moves away from the implicitly heteronormative, erotic imagery of creative genius. It is worth noting that both Minerva (born parthenogenetically from Zeus’s forehead) and the Virgin Mary are examples of non-sexual reproduction.

The imagery of female collaboration in Christine’s book is the product of real-life collaboration between women, and of Christine’s passionate advocacy of the credibility of women as more than the objects of male desire. Unlike Jean de Meun, whose female artist Jeanne de Montbaston is almost forgotten by history, Christine makes sure that her readers know who it was that created some of the most famous images of her. Christine stresses the skill and importance of women artists as serious professionals. Her preferred illustrator was a woman, whom she praises warmly.

“I know a woman today, named Anastasia, who is so learned and skilled in painting manuscript borders and miniature backgrounds that one cannot find an artisan in all the city of Paris – where the best in the world are found – who can surpass her, nor who can paint flowers and details as delicately as she does, nor whose work is more highly esteemed, no matter how rich or precious the book is. People cannot stop talking about her. And I know this from experience, for she has executed several things for me, which stand out among the ornamental borders of the great masters.”

(from The Book of The City of Ladies)

Christine’s praise is part of her case against contemporary misogyny, but it’s also concrete evidence of networks of female support and cooperation, even in the male-dominated context of bookmaking. The portraits of Christine gives her authority by picturing her as a compound of personified ‘Lady Wisdom’ and of the Virgin. Christine’s words returned the favour. In modern terms, Christine and Anastasia’s partnership – each promoting the other as a credible professional – is not dissimilar to our own networks of women supporting each other.

Did Christine and Anastasia know Jeanne de Montbaston, the often-overlooked fourth participant in this sprawling debate over male and female creativity? It’s possible. Although Jean de Meun died in 1305, his artist Jeanne and her husband were living and working in Paris at the end of the fourteenth century. Paris was a large city at the time, but guilds of artists were tightly controlled, and two female illuminators both living and working in the same place at around the same time may well have known each other, and each other’s work. Were Christine and Anastasia supportive of Jeanne? Amused by her part in shaping responses to the Romance of the Rose? Did she know of Christine’s work? We may never know.

I started writing this blog because a network of supportive women encouraged me. It was a baptism of fire, because I knew that if I didn’t push myself, I wouldn’t keep at it. So, for this past week, I’ve done seven posts in seven days. I couldn’t have done it without supportive networks, and I am very grateful to everyone who’s cheered me on or shown me how to make the blog better.

Thank you.

Update: I should stress that this post is partly speculative. We don’t know much about Anastasia, other than what Christine says, although we do know that Christine worked closely with her illuminators to produce her manuscripts.

I can’t help feeling there must be a novel about Anastasia, Jeanne, and late-medieval Paris for someone, though!