This is how I imagine Jon Snow would die. You know nothing, John Snow.

The Hague, KB, KA 20, f. 34r. From this site.

This is an unashamedly geeky post, which I writing because it’s hot, and I’ve been doing a lot of proofreading, and because I enjoyed writing about Game of Thrones, misogyny and medieval romance last time. I’ve had a question from Rachel Moss (tweeting over on @WetheHumanities today) going round and round in my head today. She was talking about the popularity of the medieval era for fiction writers, and asked ‘What is it about the Middle Ages than encourages people to use it for fantasy?’

As I was thinking about this question, I came across this piece, titled ‘Why “Game of Thrones” Isn’t Medieval, and Why That Matters’. Now, normally, that title would make my heart sing, because I am fed up with the lazy justifications of G. R. R. M.’s misogyny as ‘just the way it was back in the Dark Ages’. There were some nice points in the article about how Martin picks different technologies from different eras. And I liked the point that, aesthetically, Game of Thrones is closer to Victorian romanticism of the medieval, than to the medieval itself. But, unfortunately, so is this article.

The author, Breen, puts forward the argument, basically, that Martin’s world isn’t medieval because it’s too technologically and scientifically advanced. The majority of Martin’s world, he argues “belong[s] to what historians call the ‘early modern’ period”.

I admit, in my fantasy world, there will be some kind of cosmic retribution system for anyone who uses the phrase ‘what historians call the [insert name] period’. I’ve never seen two historians agree unreservedly on the limits of pretty much any historical period, and when they do, you can be damn sure they won’t be talking about the medieval/early Modern division. But here’s what the author describes as being definitively post-medieval in Martin’s world:

“Seven large kingdoms, each with multiple cities and towns, share a populous continent. Urban traders ply the Narrow Sea in galleys, carrying cargoes of wine, grains, and other commodities to the merchants of the Free Cities in the east. Slavers raid the southern continent and force slaves to work as miners, farmers, or household servants. There is a powerful bank based in the Venice-like independent republic of Braavos. A guild in Qarth dominates the international spice trade. Black-gowned, Jesuit-like “Maesters” create medicines, study the secrets of the human body, and use “far-eyes” (telescopes) to observe the stars. In King’s Landing, lords peruse sizable libraries and alchemists experiment with chemical reactions and napalm-like fires. New religions from across the sea threaten old beliefs; meanwhile, many in the ruling elite are closet atheists. And politically, in the aftermath of the Mad King and Joffrey, the downsides of hereditary monarchy are growing more obvious with every passing day.”

These early fourteenth-century Lincolnshire folks better not be drinking wine before they’ve learned to import it!

London, BL, MS Add. 42130, f. 208

So: what makes a world post-medieval is good trade networks, navigation, urbanisation, scientific inquiry, religious diversity, and growing disinclination for hereditary monarchy (no one told Henry VIII about that last one, did they?). To me, a lot of this sounded rather like the Roman Empire, but I’m no Classicist (and I couldn’t think of a parallel to the Iron Bank). I couldn’t really see how any of it was distinctively post-medieval, as opposed to fifteenth-century English, and I’m inclined to think the Braavosi are Lombard bankers, or maybe the Florentines who’d financed Edward III’s wars back in the fourteenth century.

However, Breen goes on, rather disingenuously I thought, to discount the fifteenth century that Martin claims to be drawing upon, and to look at the High Middle Ages:

“A world that actually reflected daily life in the High Middle Ages (12th-century Europe) would be one without large cities or global networks. A diversity of religions would be inconceivable. Many aristocrats wouldn’t be able to read, let alone maintain large libraries. And no one would even know about the continents across the ocean.”

What Daenerys has in store for the wildlings. London, BL, Royal MS 12 C XIX, f. 62r. Note: I’m showing you elephants for a reason …

Because I’m nice, I’ll accept that what the author means by ‘large cities’ and ‘large libraries’ isn’t defined, so he may have a point. That said, wiki (yes, I’m citing wiki. You’ll live) reckons the population of Paris in 1200 was about 110,000. In 1530 (‘early Modern’ according to the author), the population of London was about 50,000. The point about many aristocrats being unable to read is one that makes me want to curl up and whimper in a darkened room, and I accept that’s one of the inevitable side effects of writing 90,000 words on medieval reading and calling it work. But it’s the claims about religion and geographic knowledge that get me the most.

For starters, let’s look at what medieval Europe knew about continents across the sea and ‘global networks’. Twelfth-century England knew that Africa existed – there’s a brilliant series of books called The Image of the Black in Western Art, which demonstrate that true-to-life images of black Africans made their way into Western Art at a pretty early stage. They knew of the more distant reaches of the Islamic world, to a surprisingly detailed degree. I came across this lovely article about Arabic influences on medieval England, which claims the earliest Arabic-English loan word to be the Old English word ‘ealfara’. In the Anglo-Norman romance Boeve de Hamtoun, written sometime around the last decade of the twelfth century, hero explains:

“I was in Nubia, and Carthage, and the land of the Slavs, and at the Dry Tree, and in Barbary [North Africa], and Macedonia ….”

(quoted from Dorothee Metzlitzki, The Matter of Araby in Medieval England (London: Yale University Press, 130).

As this quotation might remind you, England was a nation familiar with the Crusades, which necessitated contact with Islamic religion and culture, but that’s not the only way in which the idea that twelfth-century England was a religious monoculture is inaccurate. At the beginning of the twelfth century, in England, there were basically two religions you’d expect most people to belong to: Christian (majority) or Jewish (minority). It also seems likely, looking at the prohibitions against witchcraft and superstition you find, that there were also people whose beliefs and practises were, at the very least, not exactly theologically orthodox Christianity. I don’t really study the twelfth century, but when I do, I’m always struck by the extent to which scholars were working with concepts not only from Christianity, but also from Judaism and Islam. In fact, this period is sometimes called the ‘twelfth century Renaissance’ because the rapid changes to intellectual life and culture marked a kind of ‘rebirth’ of learning. This book is just slightly later, but check it out – it’s Euclid’s mathematical textbook, written originally in Greek, translated into Arabic, and, in this thirteenth-century version, into Latin. How’s that for networking?!

As you might expect – and appropriately in the context of Game of Thrones – there are some rather horrible downsides to this era. For starters, anti-semitism seems to have been predictably present, leading up to the official explusion of the Jewish people from England at the end of the thirteenth century, and including the notorious massacre of York’s Jewish population in 1190. Slavery – both of serfs who were born into a system of extremely limited rights, and of foreign captives or trafficked men and women – isn’t a uniquely early Modern phenomenon either. The Vikings, when they weren’t busy journeying to Constantinople and being part of the Varangian Guard, were enthusiastic slave traders. In short, twelfth-century England (and Europe) had both the good and the bad bits of what the author of this article believes to be uniquely post-medieval about George R. R. Martin’s pseudo-medieval fantasy.

And I think it’s this – the genuine nuance of medieval England, the complicated, mixed-up world where people were both barbarically anti-semitic and intellectually fascinated by Arabic and Hebrew learning, where merchants traded with Africa yet also looked at maps that placed black men alongside monsters on the edges of the world – that the author of this article can’t get to grips with.

Concluding the article, he observes:

“as Martin’s books progress, we find that his is a world where women and people of color struggle to gain leadership roles, where religious diversity (if not toleration) proliferates, where characters debate the ethics of abetting slave labor, and where banks play shady roles in global politics.

Sound familiar?”

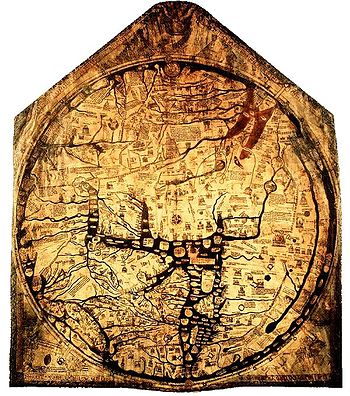

Breen’s argument singles these aspects of Martin’s narrative as historical anomalies, things unheard of prior to the early Modern world. He relies for contrast on a fantasy version of medieval Europe, a fantasy of the primitive world that lies beyond the world we know, just as monsters and dragons lie at the edges of medieval mappaemundi, beyond the borders of the known world.

Yet, these maps were made not as cartography, but as religious idealism: they do not represent the world as medieval people knew it, but the world as the medieval Church wanted to imagine it. This fantasy glosses over the complexity of the Middle Ages under the guise of interest in ‘strong women’ or ‘women and people of colour as leaders’.

I get that this is a nice trendy argument. We love historical fantasy because it offers up to us an unflinchingly grim perspective on our own struggles. It might be unfair to speculate that it’s particularly common for right-on leftie white men to appreciate such unflinching, grim perspective, perhaps because it’s less of a novelty to the rest of us? The problem is, I suspect you can make the same observations about pretty much any period of history. Can you imagine a time when women and people of colour decided, en masse and without exception, ‘ah, heck, let’s just accept our destinies and keep our heads down’? No, me either. Though I can think of plenty of periods in which rather more scholarship has been devoted to noble white men who worked to free slaves and emancipate women, than to the slaves, ex-slaves and women who worked alongside them.

Actually one of the things that intrigues me about the GOT universe, and I’ve not seen discussed, is how it could possibly remain in the medieval period (or whatever) for so long?

From what little I know in our own world there was a steady progression of technological evolution from the early medieval (ca 5thC?) to the late (15thC?), so a 1000 years at most. And the technology available in the late middle ages was vastly advanced over the early period. Of course it’s not like today where post industrial revolution and capitalism we aggressively develop new technologies, but even so I think it’s intriguing to speculate how it could have got stuck in a rut for the three or four thousand years or more.

While it’s possible to envisage a neolithic civilization persisting for that period, there’s no obvious brake on this one. Magic exists, but seems rare, and dragons haven’t been seen for 300 years. Indeed the feuding on the various houses is precisely the sort of thing that advances technology. There’s the long seasons of course, but you’d have thought that would have pushed innovation, not restrained it.

GRRM can do whatever he likes with his universe, but it does seem a little odd

Ooh, that’s really interesting and I’d not thought about it.

I’d felt that GoT characters have a really strong sense of how much things have changed in the (fairly) recent past – they know they haven’t got Valerian steel technology as standard, that sort of thing? It reminds me more of Anglo-Saxons wondering about the Roman ruins and how on earth they built them, than anything much later. But then, I wonder how much ordinary people notice change in a civilization where communication technology is quite basic? I can believe that both in Martin’s world and in medieval England, many people would have been completely unaware that changes in navigation that were going to be revolutionary, were starting. So maybe that is why it feels quite static?

To me, it’s a welcome change from those really terrible historical novels where some character is constantly popping up to marvel at how s/he lives in an age of invention … and generally said character is perfectly clued up on every single ‘important’ technological change of the era, too …

The middle ages were slow in spreading inventions. And they were often proprietary, just as Martial Arts were a few continents away. So, yeah, it feels slow.

Were they? I don’t really think so – which inventions? I don’t think that the concept of proprietary technology is widespread in medieval England (though of course I don’t know about elsewhere). But I’d like to know which inventions you’re thinking of, as I do think Martin must have a pattern to how he writes different types of invention.

Jeanne,

much of the spread of medieval inventions came through monks — but they kept their inventions to themselves, often enough.

http://listverse.com/2007/09/22/top-10-inventions-of-the-middle-ages/ Note the four century quasi-monopoly of monks

And guilds did a lot to slow innovation too.

Plus, a lot of GREAT inventions (STEEL!) weren’t understood, at all. The Vikings and Scandinavians produced the best steel (dirty, dirty shops!), but they didn’t know how, so they couldn’t teach others (and wouldn’t have wanted to, as it gave them a military advantage).

I’m not really sure about that, Mian. Certainly in England, monasteries are pretty closely involved with their communities. On your link, plenty of those innovations aren’t exclusive to monasteries at all.

With the guilds, I think there’s more of a case. Though I wonder, because the presence of so many angry complaints by guilds that someone unlicensed was trespassing on their turf would suggest that people outside the guilds perhaps did know what to do – they were just prevented from doing it.

I do think you’re right that many inventions (all through history, not just in the Middle Ages) have been misunderstood or only partly understood, long before they were fully successful.

Isn’t it intriguing when you think about it? Certainly agree about the characters not noticing change, that fits with life in our medieval world where a peasant would be born and die without noticing much different if anything over their lifetime, that does work nicely. It’s not that I have a problem that GOT is set in period X, it’s just X seems to have been around a very very long time.

A couple jump out at me. Firstly gunpowder – you only need charcoal, saltpetre and sulphur to produce that – the first two have to exist and it’s hard to see how the third cannot. Once you have gunpowder and cast iron you have cannon, and although the progression takes time cannon are so useful in reducing fortifications that progress seems inevitable. Second is steam engines, which require even less resources. GOT doesn’t seem to have that much of a slave population (the usual argument why steam engines didn’t progress in ancient Greece) and they certainly will have mines that require pumping. So how can a civilization have not noticed a kettle boiling for so very long?

It’s not as if they don’t have alchemists, so there’s obviously some people doing primitive science and there’s not a ban on it. And I have no idea if they have printing – whole lot of questions there too.

There are some parallels I guess, China has been a recognisable single civilization for three thousand years or more (but usually with a strong central authority, which GOT doesn’t have) and Japan of course banned firearms for a hundred years, but again the ethos behind that doesn’t fit with Westros.

OK, I know I’m being totally geeky trying to poke holes in something which is purely invented as entertainment and doesn’t have to follow any rules, but the internal logic is quite intriguing when reflected back on our own – could western civilization have progressed through technologies at a slower pace, if for instance it didn’t have Islamic societies to borrow from? How much is because trade in the European North developed ocean capable ships? Interesting stuff I think.

Oh, but being geeky is half the fun! Whenever I love something, I always want to get into the nitty-gritty.

I wonder if maybe it’s a slightly Tolkienesque issue? Tolkien casts industrialisation as bad, and maybe Martin figures it’s easier just to edit out some of those technological aspects.

I think Western civilization would certainly have been *much* slower without Islam to borrow things from. This is a digression (and I don’t know where in the world you’re writing from), but just recently a historian called David Starkey, here in the UK, has made an idiot of himself by saying some unpleasant and, frankly, racist things about the Middle East and about British Muslims. It really made me angry and it made me think how much medieval Europe owned to that civilization, so I’m really glad you brought that up.

I do think the geographic/racial stuff is Martin’s weak point. It’s hard for me to put Quarth, the Dothraki and Braavos into any sort of context really. But, who knows? Maybe he’s got a clever plan …

Martin’s Dothraki map pretty nicely to the Turkish hordes (they come in all colors, and all races, because the Dothraki take all sorts of slaves). Braavos feels like Venice,

Thanks for the essay, I appreciated reading it. However, from the title I was expecting something a little different. I don’t think Game of Thrones is nearly as historical as people would like to claim, and I think that gap is ignored in the service of male fantasies.

The problem with regarding Game of Thrones as a semi-historical brand of fantasy is not that the cities are too large–as you’ve shown–it’s that the show/books skimp on the civic, legal, and social development that should coexist alongside large cities. For example, if the story draws on the War of the Roses, where are the lawyers? Or high-ranking members of the clergy? Largely absent from the show are the people and professions that would have had a vested interest in curtailing a violent civil war.* Their absence is important because large cities, Seven Kingdoms, and global trade routes don’t exist without them and their stabilizing effect. By removing them, GoT implies that its society, whatever the specific historic parallel, was built and is now held together primarily by violent, aggressive, and conniving men and women.

That’s not drawing on historical material, that’s making a statement about human nature and burying it in history (or in this case, historically inspired fantasy) to make it seem more genuine. The problem with history in GoT is not the architecture or science is early modern or more recent, it’s that it uses a complex Medieval society as the backdrop for intense interpersonal violence that’s from the Dark Ages.** GoT’s sleight of hand is to convince its audience that rulers will personally spill this much blood and yet still rule over anything other than ruins.

This sleight of hand serves fantasy, and male fantasy in particular. It sells the idea that if society wasn’t holding them back, men could take whatever they want, whether it’s power, wealth, or women. It’s not terribly different from the aggression and resentment that comes from men’s rights activists (“if only it weren’t for feminist social customs, I could get a girl”). While GoT certainly has it shares of worthy female protagonists, and quite a few alpha males get what’s coming to them, a good deal of the action still centers around men taking what they want with very little social consequence.

The issue is not that the show is this violent, or that it depicts medieval society in a particular way. It’s that the show depicts those two things together, and gives the impression that you can have a violent society that also has the time and energy to make the beautiful cities, armor, weapons, clothes, etc. All of these props are necessary to sell the fantasy.

It’d be one thing if GoT did this and people called it fantasy. Instead, they insist on calling it semi-historical or historical medieval fantasy. Instead of debating whether or not it’s really drawing on early modern or medieval history, turn that label around: people want to think of Game of Thrones as being historical medieval fantasy. They want this fantasy story to depict what medieval life was like. Calling it historical fantasy makes the lessons of GoT more real. Obviously, GoT won’t make dragons more real. However, it can make the violence, interpersonal relationships, etc. more real.

it’s worth noting that when that process plays out, it’s not the background details that GoT makes real. Very few people in the audience are going to pick up on the particulars of world systems in GoT. The stuff that will make the biggest impression are the scenes that are the most concrete: the violence, sex, and scheming. By calling it historical, GoT audience believes that we were like that in our past and, if it weren’t for modern society, we could be like that again.

* (Something similar happens with farmers. We’re meant to believe that they have an agricultural system that can support a large kingdom with multiple huge cities, but from the few glimpses we get of the farmers they are weak and totally at the mercy of other people.)

** (I know that term’s out of favor in historical circles, but I use it here to emphasize that it’s peoples impressions that we talk about).

Hello!

Yes, probably could have been a better title. I absolutely agree that GoT isn’t historical, and that the gap is ignored for that reason. I’m coming round to the idea that the least historical thing about it is the geography/navigation of the world, which is why I ended up discussing that. I think a lot of people have an image of the medieval world as insular and settled, so that war would come as a total shock and upheaval (as it does in GoT). I don’t really buy that.

I find it hard to know whether that’s something people believe about ‘the Dark Ages’ (yes, I do hate that term), but I think our society is very invested in imagining the medieval world as violent and primitive.

I agree with you about farmers, lawyers and so on. You get a tiny glimpse with Bran while he’s ruling Winterfell and listening to the requests of his tenant landholders, but that’s all I can think of. But again, I think it comes back to geography: Martin’s world is full of wildernesses. If it were medieval England, I think it would have far more woods that were royal/noble parks, and far more evidence of agricultural land.

War doesn’t come as a total shock and upheaval, except in the North, where they’re understandably bound together by shared “It’s crummy up here” (kind of like Russia).

This civilization has seen 2 major wars in the past 20-30 years. That’s not coming out of the blue.

Other than the “navigation” managing to get people across “The Narrow Sea”, I don’t have much problem with it. The Italians and Arabs were at least mediocre seafarers…

And the clergy are coming, god save their souls. [Guilds and other powerful Third Estate do seem notably absent. Perhaps due to the Boom and Bust nature of moneyed wealth in a place where seasons fluctuate so harshly?]

Oh … that’s funny, to me, it seemed only the North was prepared. Robb Stark seems to have been brought up to know his own recent history, and he’s limiting his demands based on that understanding. I feel that what happens to Winterfell is one of the major twists, really, because it looks so cynical and well-prepared, but even so, a couple of twists of fate and it’s shattered (whereas Lisa Arryn, who patently can hardly believe what day it is, is unscathed).

I think what you say about fluctuating seasons and their effect is so true! See, *this* is the sort of thing that makes me really admire Martin. Sure, I can criticize him all over the shop, but he includes details that genuinely make you think ‘hmm, maybe I ^can’t^ assume this fictional world is predictable’. I think that’s such a clever way of writing.

Jeanne,

yeah, the other thing about Martin is that he’s fairly slow about bringing in factions (got to give us time to know them). Come to think of it, Magister Illyrio is a wealthy man, and a trader. He’s part of the third estate too.

… in that case, you’ll find that the third estate is around, and is busy manipulating things behind the scenes — and they’re not fond of war. [Also the Maesters…]

I’m actually not sure how much the “shadow powers that be” actually are manipulating the Grande Game (the one with Dragons and White Walkers)… If they’re aware, and playing the broader game, it may make sense for them to be allowing much more warfare than is currently profitable.

Yes, will be so interesting to see what he comes up with next!

RW,

when people say Martin is “more historical” … they mean in the Rolemaster versus D&D sense.

His “women in chainmail” (Brienne) actually can swing a damn broadsword. They’ve got the height and musculature for it.

And women who can’t? Learn other methods of fighting (Cloak and Dagger style!).

I don’t think this is a series that is much about cherishing alphas, or any of that neanderthal (Neanderthals were nice people!) bullshit. It’s much more about rooting for the small and weak.

The Clergy are coming! I promise!

Oh, no, they don’t! You would not believe it, but there are people who seriously argue Game of Thrones is pretty much medieval England.

That said, I’m not convinced Martin doesn’t cherish alphas. I think he would like very much to write a series where he doesn’t, but he falls for his characters more than he’d like, perhaps? But again, that’s part of what I find so fascinating, that really good popular fiction can keep everyone guessing because we do believe the author is as caught up as us.

Oh, and thank you for all your comments! Forgot to say that. 🙂

Jeanne,

some people will do that on the strength that there are Starks (Yorks) and Lannisters (Lancastrians).

… which, to the extent that it is modeled after the War of the Roses, sure. Tyrion’s a fair patch for Richard the Third, if treated MUCH more gently than Shakespeare did.

It’s his style to write so we can understand everyone. But Drogo dies, Robert dies, Robb dies. All the alphas die — through folly and overconfidence, and who is left? The small and meek, struggling to get by.

Mmm. Still not convinced, really. But we shall see!

Reblogged this on History Mine and commented:

A really interesting blog, and as a student of ancient history, it is interesting to see how many of these concepts can be pushed even further back.

Hello, I wonder whether you’ve seen history-behind-game-of-thrones.com? It looks at individual aspects from the story and compares them with a number of real-world parallels. It might be of interest. I would agree with most of the points about the strange rate of progress. I wrote a guest blog for ‘History Behind…’ and I had to point out that the Night’s Watch has existed for 8,000 years; far longer than any military order, or even civilization, has existed in our world. On the other hand, there is some innovation. I can only think of one instance; when Joffrey explains that he has developed a new loading process for his treasured crossbows. IRL, this sped up the loading of the weapons, and made them a more effective tool of warfare. Fate snatched the inventor king too young (potential sarcasm).

Ooh, I shall have a look at that site. Thanks! I saw you’re an Ancient History student – my husband’s degree is in Ancient History, so I’m really interested in that. He’d felt the same about how (abnormally) long some things seem to stay stable in Martin’s world. Though I suppose it could be (thoroughly medieval) self-mythologising on the part of the Night’s Watch? Tricky to see how they’d fake Sam’s knife, though …

I’d not thought about Joffrey and innovation – ouch! I think the ‘Martin doesn’t like technology much’ theory is shaping up!

Thanks for your comment!

I definitely get an Arabic/Romanish flair from Essos (along with the Italian “city state” motif)

From the hints GRRM leaves in the novels, my sense is that the world used to be *much* more magical. There is no other explanation for much of the construction we see in Westeros and Essos except for magic. The Wall is larger than any man-made structure in our world; the Colossus of Bravos is too; and the Eyrie would have been nigh-impossible to build without magic, and makes far more sense as a fortress when you remember that the Aryns supposedly used to go to war riding giant eagles.

Thus what differs it from our world is that with the fall of the ersatz Rome (Valyria), they lost magical knowledge not technical knowledge. Valyrian steel isn’t a lost technology, it’s a lost enchantment. And I think the extended Medievalism of the world is because magic has been holding science back. It’s only with the death of the last dragons a few decades prior that technology could develop.

In any event, all discussion of the historicity of Westeros is made ridiculous by the fact that Martin did not adapt the flora and fauna of Westeros to the weather. In the real world, regions that have extended hot dry spells and extended cold spells don’t have forests – they have small, tough, shrubs. Westeros looks like England and it should look more like Alaska or Mongolia.

Oh, that’s so true.

I think this is when ‘magic’ becomes unsatisfying in fiction, isn’t it? We can’t really sympathise with it as an explanation. I think magic works best when it is barely perceptible, and worst when it’s an ‘and then I woke up and it was all a dream’ style of plot rescue.

Check out Kulthea… Magic works best when science is impossible because the rules, while predictable, are too hard for mortal mind to divine… Imagine a world where gravity, or friction, only worked sporadically?

Essos gets the hot dry spells, and is appropriately resembling of the “Great American Desert” (that being the High Plains).

The North of Westeros shouldn’t look like England so much as taiga… the great Northern Canadian Evergreen forests…

It’s only where you get piles of snow and permafrost that you get true tundra.

Meant to mention: you get a bit more of the dark age flair with Sansa and Arya making their own embroidery (and sewing their dresses)…It’s still an era where stuff is made close to home (Winterfell has its own armorer/smith)