Roberta Magnani just raised the question of how people use academic blogs over on twitter, and I am mainly writing this because it’s not a 140-character answer, but also because it’s a question I’ve been asked fairly regularly, so it might be useful.

I started blogging in the dead time between submitting my PhD thesis, and getting to my viva. I knew I wanted to change direction in my research, and I knew I wanted my new research to fit together more naturally with all the feminist reading and writing I’d been doing more and more of in my day-to-day life. I already knew, at this point, that I write best when I’ve been talking to people (or, realistically, writing to people) and translating my thoughts out of academic prose (or what I thought was academic prose back then) and into something everyone can read and understand. I knew a couple of people who blogged – not academic bloggers, though – and I followed their tips to start with. Some worked, and some didn’t, but here’s what I learned along the way. All of my tips are specific to the the kind of academic blogger I am (a medievalist feminist), but you could adapt to other disciplines easily.

- Justify your time blogging. It has to be useful or its wasted time. So, the first pieces you write (and the pieces you write when you’re stuck) should be pieces of thinking you need to do for your other work. Maybe you need to read a particular text and you’ve been putting it off? Write a review. Maybe you need to figure out why you keep coming back to a certain passage? Do a close reading. I am still incorporating bits of early blogging into work I’m submitting to publishers, because it was useful.

- Get your voice out. Get on twitter, get onto facebook. On twitter, follow lots of interesting people. Talk to them (nicely). Share their interesting posts. Respond to them. Share your posts. I share 3-4 times a day for the first 24hrs after posting (when I can remember). Twitter will even tell you which tweets get the biggest response, so you can figure out what times work best. For me, it’s around 8am (morning commute) and 10pm (US readers/UK night owls). Getting lots of clicks is nice, of course, but the point is that you get responses. I never get a lot of replies to blog posts – I’ve had well over 100,000 views on the blog, and a tiny handful of that number reply – but far more people will comment on a FB link or reply or twitter, or even just email me.

- Make connections that work both ways. People will respond to you, so respond to them. A couple of years ago, I wrote a blog which a professor I’d never met read. She asked me to work it up into a conference paper proposal (that was NCS 2016). I wrote a couple of blogs for her. One of my students saw one of these blogs, and asked me about writing an essay on the topic. I read that essay, and it helped me push my work-in-progress book in a new direction. And so it goes on. I know a big circle of academics because I blog and they blog. It’s a conversation.

- Write regularly. I know people write blogs they pick up and drop at a whim, but I don’t think it works very well. If you’re going to be busy, take a blog break and say so! But then, come back and say if you’ve finished for good. It looks more professional, but it also organises your mind so you don’t keep thinking guiltily ‘hmm, I used to write stuff here’. Set yourself a target (mine used to be once every two weeks and is now once a month). Achieve it. Which takes me to the next point:

- Use the blog to break writers’ block. It isn’t an academic paper. You can just witter. And if it’s bad, it doesn’t matter. Just do it, share it, and get some responses to cheer you up. When you’re in the depths of block-jail, even a couple of nice kind people sharing a post on twitter will make you feel less inert. If you get into this habit, it will become second-nature. Get used to blogging right now, not as something you put in the calendar to do tomorrow.

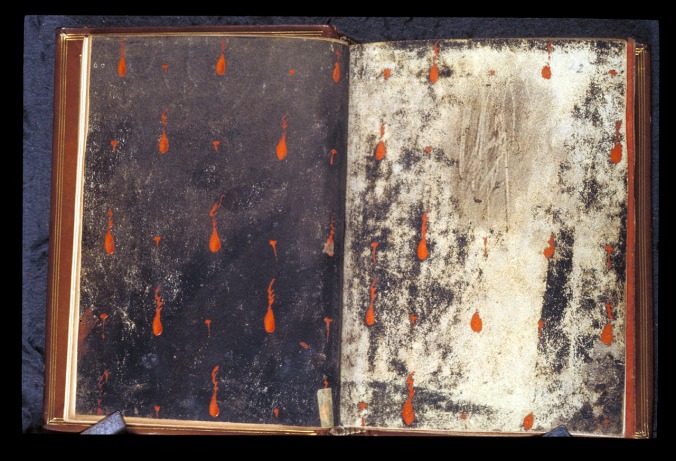

- Vary the types of post you do. Try a long-read style one, where you really pay attention to the way you write. Try a rant. Try playing with images or quotations. See what feels most natural and what you want to do more of. A mix of short and long pieces will get different readers interested, but it’ll also help you sort out your own academic style (mine has changed a lot since I started blogging, and I am now delighted to say that I was able to work a cunnilingus pun into an academic paper with nary a blush. It’s these things that truly move the scholarship forward, don’t you feel?).

- Match the blog with teaching and lecturing. Test out a new idea for a lecture on the blog. Write up that lecture that didn’t quite work as a blog post. Answer those questions that were fascinating but too big to answer in five minutes at the end. Ask other people what they do – you can do a lot of reflecting on pedagogy in a blog, but:

- Be kind and be professional. You cannot whinge about students on your blog. Or really anywhere else they might read it. It’s unprofessional and rude and unnecessary. And it makes you look like a really, really bad teacher. Instead:

- Use your blog to defend your students. Students get a lot of bad press. That doesn’t mean you have to be uncritical, but you can be dispassionate and considered about it. Use your blog to defend colleagues (especially ones you don’t know whom you’ve seen get an unjustified kicking). Use it to defend other writers outside academia. Even if those people never read what you write (they probably won’t), it’ll help you articulate to yourself where you stand. It will make you a more politicised teacher and writer.

- Change your mind in print. Blogging’s great for that. Get used to changing your mind, linking to the old piece where you said one thing, and tearing it down. Because it’s going to happen in other, more scholarly forms of print media, so it might as well happen here first.

I really value my blog. It provided me with the raw drafts of about 40-60 lectures I didn’t have time to write (thank god for using that dead time pre-viva!), and almost every chapter of my new book has ancestors in blog posts. Every conference paper I’ve given since submitting my PhD has had its origins on here. And yes, I put my blog on my academic CV, too.

Update:

Number 11 on the list is: know when to stop. If you can’t write a blog post in 20 minutes, 30 tops, stop. You might very well come back to it, especially if it’s a long read type of post, but don’t spend ages blogging. This is something I have got much, much better at – my early posts took hours – and I am still bad at it when I’m writing for someone else.