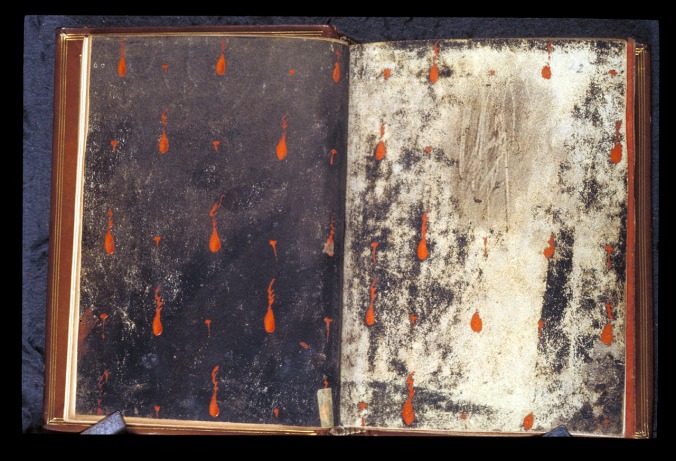

London, British Library, Egerton MS 1821, ff. 1v-2r

I was thinking, this morning, how there is never enough time for some things. 82 years, for instance, feels like far too little time – even though I had been expecting to read that Leonard Cohen had died every time I saw his name in the depressing little facebook ‘sidebar of 2016 shitshows’ that has evolved over the course of this year.

The image above – the opening pages of a medieval prayerbook made in the fifteenth century – came up in my teaching today. We were reading Julian of Norwich and talking, amongst other things, about the grotesque, weirdly solid droplets of blood she visualises – like the scales of a fish – dropping down Christ’s face as he dies on the cross. Medieval literature is very keen on blood, sweat and tears, as the image demonstrates. They flow, drip, trickle, spurt, smear and gush from text to text and (revoltingly, but historically and scientifically verifiably) across the pages of stained, damp-puckered, grimy manuscripts that have plainly caught the worst of human effluvia over the centuries. Such tears can seem both overwhelming, and off-putting. Margery Kempe weeps so often and so loudly that (she proudly records) onlookers frequently presume her to be drunk in church. Piers Plowman‘s Will wails so prolifically that he exhausts himself into deep sleep. Chaucer’s Troilus experiences what should be temporary sexual frustration as a fully realised episode cardiac and sanguinary gushing.

But blood, sweat and tears are also, depressingly, part of the experience of studying medieval literature at university. Echoing both medieval imagery of tears and the medieval love of sensory contact with books with impressive authenticity, a student describes how

‘[Y]ou open the book you’ve probably borrowed from the library. You are hit by the smell of the tears of thousands of other[s] … who have had to endure the same pain.

This idea of being caught in a tradition of academic suffering is not unique to Cambridge. When I started my Masters at Oxford (which is, admittedly, not a million miles from Cambridge in ethos), I read a helpful guide to the process, written by an academic. It mentioned – with no apparent hint of irony or humour – that a likely consequence of nine months of intensive study of English Literature was (I kid you not) ‘the dark night of the soul’. Both pieces of writing reminded me of an article by Mary Carruthers, which begins with the bizarre religious writings of the medieval theologian Peter of Celle. Peter wrote a book called On Affliction and Reading, which sounds suitably negative. By ‘affliction,’ Carruthers explains, Peter means:

examination of conscience … oral confession, flooding tears, mortification, kneeling in continuous silence, psalmody, and lashing.

Peter goes on to describe what the ‘reading’ part of his topic requires: not only mind-numbing repetition, carried out in the lonely narrowness of the monastic cell, but also something akin to physical torture. It is reading that lacerates the flesh, strips skin and muscles from the underlying bone, and tears at the body until the blood flows. It is like being in:

a market, where the butcher sells small amounts of his flesh to to God, who comes as a customer. The more of his flesh he sells, the greater grows the sum of money he sets aside. Let them, therefore, increase their spiritual wealth and fill their purse by selling their own flesh and blood, for flesh and blood will not possess the kingdom of Christ.

As Carruthers comments, what is even more distasteful is the rhetoric of commodification, for the process is a lucrative transaction with God. However – having established this unsettling tradition in medieval theology – she acknowledges that medieval writers seemed to believe it was, at least, a kind of suffering that was necessary to gain benefits. She concludes, ultimately, that Troilus’ incessant weeping in Chaucer’s poem – weeping that’s often seen as absurd, comic, or pain annoying – is actually part of this tradition:

in Troilus, as in a great deal of medieval art, there is a deep connection between the grief and the argument, indeed, in some way the grief sets the arguing in motion … in this psychology, arguing needs an emotion like grief in order to come fully into being, to be invented and fruitfully intended in the first place, or else it remains dry and without fruit.

Plainly, Peter of Celle – and all the other medieval writers who seem to glory in the experience of thoroughly miserable, painful, and excessive reading – must have believed they actually did stand to gain something from the experience, whether we believe that gain was actual enlightenment or, more cynically, the status achieved through a virtuoso performance of suffering. But should reading hurt?

In my favourite of Leonard Cohen’s songs, he teaches his listener to:

… leave no word of discomfort

And leave no observer to mourn

But climb on your tears and be silent

Like a rose on its ladder of thorns

I love this image of tears as a structure, a process that solidifies into a scaffolding that gives you the support to be silent. I love the epithets he uses to describe body and soul, including the gorgeous phrase ‘tangle of matter and ghost’: words that echo back to the King James Bible and to medieval English. And finally, I love the lines with which Cohen ends the song, with a litany of images of renunciation and farewell that end:

Bless the continuous stutter

Of the word being made into flesh.

I have listened to these lines, and this song, a lot of times. I’ve puzzled over that image of the word ‘stuttering’ as it turns into flesh – which is an image I love, but also a profoundly weird image of creation, and an image of creation that is startlingly accepting of brokenness and what we might see as impairment. I’ve listened to it all so many times, while I was speed-reading a particularly boring, un-poetic translation of the Roman de la Rose, that the image of the rose on its ‘ladder of thorns’ has seeped, irrecoverably, into my mental map of that text. I’ve never actually looked up what the song means (or is ‘supposed’ to mean). I could have looked it up for this post – but I really didn’t, and don’t, want to. And I didn’t enjoy putting into words even the tiny little bit of a response that I’ve managed in this post. I can’t help seeing me writing (clumsily) about Leonard Cohen as something a bit like that process of tearing off one’s flesh strip by strip in order to make money: a transaction that’s excruciating and simultaneously extremely crass. I’d like to write really beautiful, crafted, self-effacing sentences that somehow let Cohen’s poetry speak for itself, unimpeded, while also saying something. I don’t have the time.

What I do have, is the mental equivalent of muscle memory. I had the experience of writing two essays a week, eight weeks a term, for three years. A lot of those essays were awful. Some of them never got handed in. Some of them weren’t complete. But they pushed me to write a lot of words, and to think about a lot of words. They pushed me to read a lot. So, I know that – if I want to, or if I ever need to – I can sit down and write 1200 words to compare the images of blood and tears, flesh torn and flesh stuttering into Resurrection, across texts written eight centuries apart. I can learn to understand those texts I love better – even if I never really think about them in an academic way – because there’s an ingrained habit of writing out, testing out, building up, new responses to every text I ‘have’ to read, however little time there might seem to be.

RIP

The Window

Why do you stand by the window

Abandoned to beauty and pride

The thorn of the night in your bosom

The spear of the age in your side

Lost in the rages of fragrance

Lost in the rags of remorse

Lost in the waves of a sickness

That loosens the high silver nerves

Oh chosen love, Oh frozen love

Oh tangle of matter and ghost

Oh darling of angels, demons and saints

And the whole broken-hearted host

Gentle this soul

And come forth from the cloud of unknowing

And kiss the cheek of the moon

The New Jerusalem glowing

Why tarry all night in the ruin

And leave no word of discomfort

And leave no observer to mourn

But climb on your tears and be silent

Like a rose on its ladder of thorns

Oh chosen love, Oh frozen love…

Then lay your rose on the fire

The fire give up to the sun

The sun give over to splendour

In the arms of the high holy one

For the holy one dreams of a letter

Dreams of a letter’s death

Oh bless the continuous stutter

Of the word being made into flesh

Oh chosen love, Oh frozen love…

Gentle this soul

Pingback: Blood, Sweat and Tears: Medieval Literature, Cambridge, and Leonard Cohen — Jeanne de Montbaston – 역사와철학출판사

Thank you.

Wonderful, thanks – I don’t know Leonard Cohen half as well as I’d like, but I’ve always been haunted by his lyrics.

Me too! I love so many of them.

“I’ll stand before the Lord of Song…”. Beautiful words, assemble of words and more words entice curousity!. Loved it. And our memory stands before Leonard Cohen.

Aren’t they?! And you say that so beautifully too. Our memory stands before him.

This was beautiful. A lovely piece of writing. I enjoyed it immensely.